Roy Cohn was certainly sure of himself. At a dinner hosted by press baron Lord Beaverbrook, the New York lawyer reached over the table uninvited and, with his fingers, picked food off Sir Winston Churchill’s plate.

It was one of Cohn’s less savoury habits – and, to add insult to injury, he informed the great man that in World War II, ‘the United States saved England’s ass’.

But bad table manners was the least of his failings. Many who crossed the cut-throat and belligerent lawyer’s path would recall the experience with a shudder. ‘You knew that when you were in Cohn’s presence, you were in the presence of pure evil,’ said one legal contemporary. ‘He was like a caged animal,’ said another. ‘If you opened the door, you knew he would come out and get you.’

The rich and famous, from cardinals to Mafia dons, flocked to the flamboyant but gnome-like Cohn, seeking his services while never asking too many questions about his crooked reputation. Many openly loathed him, although his friends and clients admired his brilliance. Cohn’s philosophy was simple: say anything you need to but win at all costs.

And he had one client – and protégé – above all. Donald Trump has made clear he was just glad they were on the same side.

‘All I can tell you is he’s been vicious to others in his protection of me,’ said Trump. ‘He’s a genius. He’s a lousy lawyer but he’s a genius.’

And that genius, it has long been claimed, taught the former US President everything he knows about dissembling, dirty tricks and ruthlessness.

Trump prefers not to dwell on his murky relationship with Cohn during his formative years as a young property developer, between 1973 and the lawyer’s death in 1986.

Now, however, he has no choice.

The Apprentice – a controversial biopic that the Trump campaign has excoriated as a cynical attempt to hurt his election hopes – has opened in US cinemas to tell voters that Trump is the man he is today only because of the sinister and manipulative Roy Cohn.

The film, which stars Jeremy Strong, who played aspiring media tycoon Kendall Roy in the TV series Succession, as Cohn, dwells gloatingly on the most lurid allegations of the two men’s relationship.

Strong says The Apprentice – which pointedly shares its name with the business reality TV series that propelled Trump to national fame and the White House – isn’t a total hatchet job.

Nonetheless, it seeks to explode the Trump mystique for his fans, showing him taking amphetamines, having liposuction and a hair transplant, and – most controversially – raping his first wife, Ivana. She claimed in a 1986 divorce deposition that he did this, but later recanted, prompting speculation she used it as a bargaining chip. Trump has always denied the charge.

Trump’s lawyers (taking a leaf out of Cohn’s book) repeatedly sent the film-makers ‘cease-and-desist’ letters, claiming the movie is ‘fake’, ‘pure garbage’ and ‘election interference’. They didn’t stop the film, but they did at least scare off some of the bigger distributors.

In a social media diatribe in the early hours of Monday morning last week, Trump himself let fly, calling the film a ‘cheap, defamatory and politically disgusting hatchet job’.

There seems little doubt that the film has been timed to cause maximum damage to his election prospects as Americans head to the polls in just 15 days. But given that the low-budget film had flopped at the US box office until Trump’s condemnation, he might have been better advised to ignore it.

Perhaps he can blame his mistake on the legacy of Cohn, who never shied from a fight either, and whose first rule – as he drums into Trump in The Apprentice – was ‘Attack, attack, attack’. Never defend and never apologise.

According to his biographers, Cohn always regarded attack as the best form of defence. When a desk clerk at Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel questioned him over an item missing from his room, Cohn tore into him, saying: ‘You’ve got a lot of nerve talking about a bath mat after you bombed Pearl Harbour!’

Fiercely anti-Communist and homophobic, he became chief counsel for the notorious red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy, and together they exposed and ruined many Left-wing and homosexual men and women during senatorial investigations in the 1950s.

In Cohn’s case, outrageous hypocrisy could be added to his long list of sins, as he was himself a closeted but promiscuous gay man who died in 1986, aged 59, of an Aids-related illness. Until the end, Cohn insisted he had liver cancer.

Armchair psychiatrists have classified Cohn, also a Jew who was virulently anti-Semitic, as self-loathing – and he was certainly full of contradictions.

Many have observed that he and Trump had much in common, only Cohn was perhaps the more intelligent. Like Trump, he’d been born and raised in New York suburban affluence as the son of a well-connected Bronx judge. So precocious was he, he finished his undergraduate and law degrees before he was 20. He lived with his mother well into adulthood.

As a lawyer, he first gained attention when he prosecuted alleged Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in a sensational 1951 trial in which they were found guilty of leaking atomic secrets to the Russians and, at Cohn’s urging, sent to the electric chair.

Cohn later reportedly admitted that, convinced of the couple’s guilt, he’d agreed to use false evidence to ensure they were convicted.

It was the first of many occasions in which Cohn would bend the law – or worse – to win a case.

While working for McCarthy, Cohn grilled alleged Communists with such ferocity that one of them afterwards committed suicide. Cohn showed no remorse.

McCarthy’s unscrupulous witch hunts were eventually condemned by Washington and his career ended in disgrace, but the wily Cohn moved back to New York and reinvented himself as the trial lawyer that no one wanted to come up against.

From 1964 to 1971, he was three times tried and acquitted of federal charges that included blackmail, extortion, bribery and fraud – only adding, some felt, to his aura of invulnerability.

He could speak for hours in court without notes, appeared to have a photographic memory and was supremely self-confident. ‘You’re almost as good as you think you are, Mr Cohn,’ a judge once waspishly told him. He reinforced his power by intimidating opponents with spurious lawsuits and empty threats.

What Cohn lacked in stature – he was 5ft 8in and weighed 10 st – he made up for with a face that screamed ‘villain’. His eyes were hooded and bloodshot, a scar trailed down his nose and his features were distorted by plastic surgery.

Some have speculated that those eyes were bloodshot because he spent so many nights carousing at New York’s notoriously debauched Studio 54 nightclub.

His reputation for winning cases earned him a fortune that he spent on a jet-set lifestyle which reportedly cost $1 million a year to maintain and included a private plane, a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce, a second home in the billionaire enclave of Greenwich, Connecticut, and a yacht called Defiance.

He rarely paid his creditors or the taxman, to the extent that Inland Revenue Service officials would wait outside his house to intercept anyone arriving with what looked like cash.

Cohn not only liked to surround himself with stuffed animals, which filled his New York home, but with attractive young men, both gay and straight. Friends diplomatically referred to the gay men as ‘Roy’s bodyguards’, while visitors were often greeted by Cohn wearing a bathrobe.

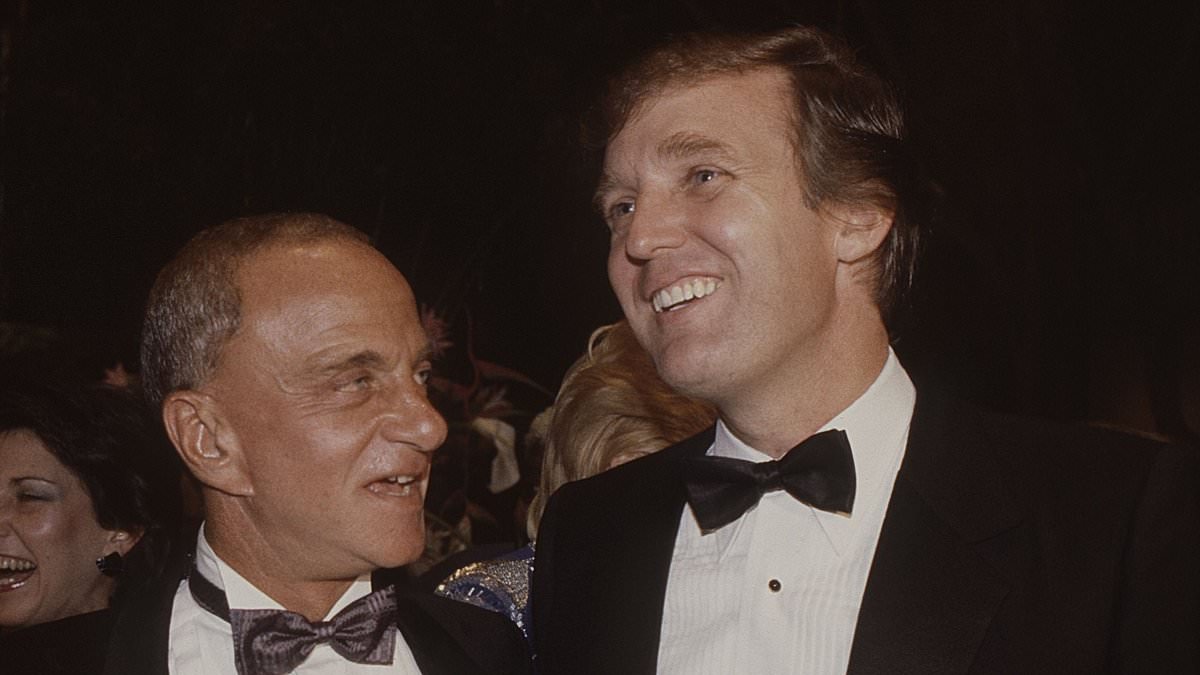

He first met Trump in a glitzy, members-only Manhattan nightclub in 1973. Trump was 27 and Cohn 43. Some believe that the lawyer’s attraction to the self-assured, strapping, blond businessman may have been partly sexual – even though the attraction was never reciprocated.

Then an aspiring tycoon trying to expand his father’s property empire and make some big deals of his own, Trump asked Cohn for his advice on a recent headache. The Trump family business had been charged with discriminating against black people.

Cohn deftly guided them out of this potential minefield (after, typically, persuading the Trumps to counter-sue his government accusers for $100 million for defamation) and Trump kept

him on as his personal legal attack-dog. Whenever negotiations stalled, he liked to pull out a photo of Cohn and ask: ‘Do you want to deal with him?’

Cohn, meanwhile, ‘could sniff out a power-to-be’, said his longtime secretary. ‘This kid is going to own New York some day,’ Cohn told a prominent gossip columnist, who had no idea who Trump was, in the early 1970s.

‘He became Donald’s mentor, his adviser on every significant aspect of his business and personal life,’ said Trump biographer Wayne Barrett. For instance, he forced Trump’s first wife, Ivana, to sign a harsh pre-nuptial agreement before their 1977 marriage, after first advising his client he was ‘better off not married’ as it would end in ‘trouble’.

Cohn would tell people that ‘Donald is my best friend’ and they reportedly talked 15 to 20 times a day, often meeting up at night at Studio 54.

Trump was a fixture at the lawyer’s huge parties, which, despite Cohn’s toxic reputation, attracted not only mobsters but judges, politicians, financiers and media barons. Cohn seemed to know everyone – his friends included Ronald Reagan, Barbara Walters, Andy Warhol, Estee Lauder and Rupert Murdoch – and he was able to guide the boy from suburban Queens around town, introducing him to people who mattered.

Trump, it is claimed, co-opted not only Cohn’s tactics but even his language, copying his boasts about being a ‘winner’. Peter Fraser, Cohn’s former lover, said: ‘I hear Roy in the things [Trump] says quite clearly. Donald was certainly his apprentice.’

They both craved attention and endlessly leaked stories to the Press. ‘I admit it, I love publicity,’ said Cohn, who liked to wear a T-shirt emblazoned with the word ‘SuperJew’ when on holiday.

Justice finally caught up with Cohn in 1986 when he was disbarred from practising law for unethical conduct.

Among his offences was tricking an 84-year-old multi-millionaire client to change his will as he lay dying in a Florida hospital.

By then, word was spreading Cohn had Aids and, according to his secretary, when Trump heard (though he denies this), he ‘dropped him like a hot potato’.

When Cohn died later that year, nearly everything was taken by the taxman. Only a pair of Bulgari diamond cufflinks Trump had given him was spared – but they reportedly turned out to be fake.

Cohn would have been so proud of his protégé.