Graphics experts have recreated the face of a pharaoh who founded the Valley of the Kings and rewrote history in ancient Egypt.

Amenhotep I – the second ruler of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty – is thought to have died 3,500 years ago at around age 35 before being painstakingly preserved through mummification.

He was the first to be buried in the Valley of the Kings – the resting site of almost all the Pharaohs of the 18th, 19th and 20th dynasties.

He was worshipped as a god after he died, primarily because he ushered Egypt into a new age of peace and prosperity during his reign.

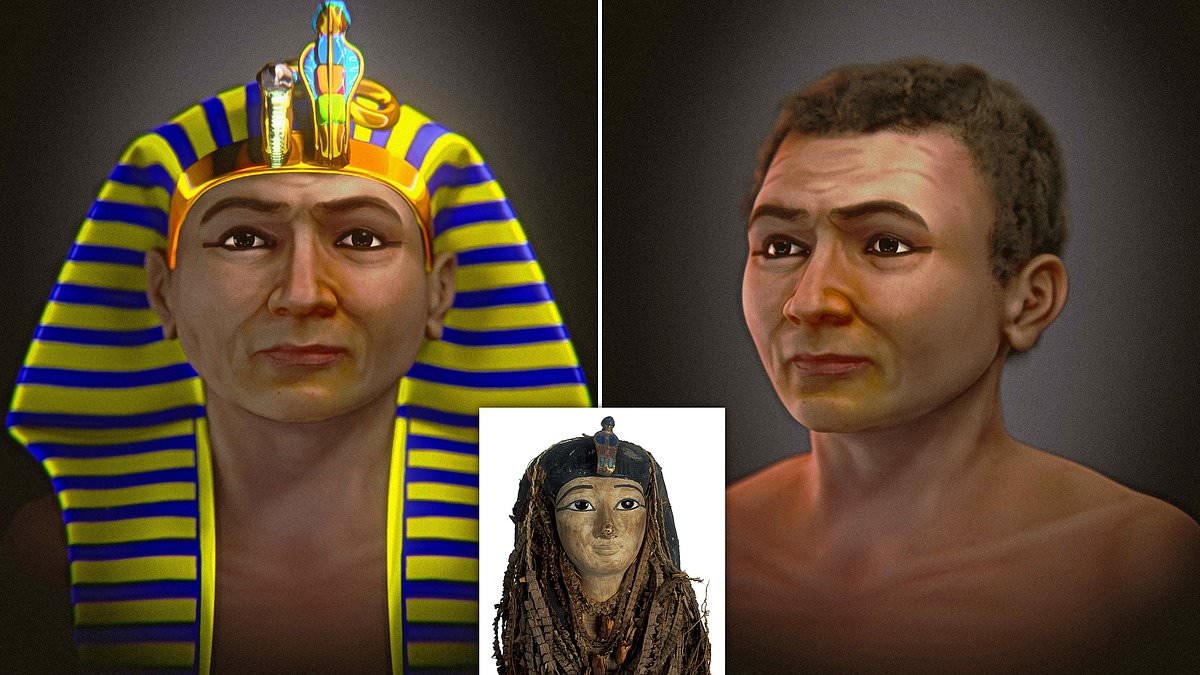

Brazilian graphics designer Cicero Moraes digitally reconstructed Amenhotep’s likeness, revealing his face for the first time in 3,500 years.

Dr Sahar Saleem, a professor of radiology at the Faculty of Medicine at Cairo University where she works on the Egyptian Mummy Project, stands beside the mummified body of the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep I as it was digitally ‘unwrapped’ with high-tech scanners back in 2021

Cicero Morares, a Brazilian 3D designer who specializes in forensic facial reconstruction, created these images by blending faces made through a variety of methods.

One method involved distributing soft tissue thickness markers across the Pharaoh’s skull, guided by computed tomography (CT) scan data from living donors.

Read More

Egypt's greatest pharaoh found over 3,000 years after his death: Long-lost sarcophagus is discovered under the floor of a monastery

Another was a technique called anatomical deformation, in which a digital recreation of a donor’s head was adjusted until the skull matched the Pharaoh’s.

This method was made possible thanks to CT scans of Amenhotep’s skull that were taken in 2021.

That work, conducted by paleo radiologist Sahar N. Saleem of the University of Cairo and Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, ‘virtually unwrapped’ Amenhotep’s mummified remains using CT scanning, and revealed details his appearance, skeletal structure and some preserved internal organs, including his heart and brain.

The scans did not indicate a cause of death, but estimated the age of death at roughly 35 years and suggested that he suffered a series of postmortem injuries ‘probably inflicted by tomb robbers or by the embalmers who re-wrapped the mummy later,’ said Morares’ co-author, archaeologist Michael Habicht of Flinders University in .

It also showed that Amenhotep stood about five and a half feet tall, his teeth were in good condition and he had curly hair, Habicht added.

Once Morares had revealed the Pharaoh’s face, he noticed that it didn’t match the god that had been depicted in statues

Many mummies, such as Amenhotep I, show an overbite. But this is generally not reflected in a compatible way in statues

‘By crossing the data from all the projections, we generated the final bust and complemented the structure with historical costume,’ Morares said.

Once Morares had revealed the Pharaoh’s face, he noticed that it didn’t match the god that had been depicted in statues.

‘Many mummies, such as Amenhotep I, show a retrognathism or overbite, and this is generally not reflected in a compatible way in the statues,’ he said.

The mummy of Amenhotep I, the first to be buried in the Valley of Kings

University of Cairo-led experts uses computed tomography (CT) scans to create 3D reconstructions of Amenhotep I

‘In general terms, the statues of Amenhotep I are compatible in the nose region, but more gracile in the glabella region and more projected in the chin region.’

Amenhotep I’s reign came in the wake of his father Ahmose I’s expulsion of the Hyksos invaders and successful reunification Egypt – and represented something of a golden age for ancient Egypt.

Not only was the ‘New Kingdom’ both prosperous and secure, but Amenhotep I also oversaw a religious building spree and successful military campaigns against both Libya and northern Sudan.

‘Under the peaceful rule of Amenhotep I, the rise of Egypt was initiated and the heyday of the New Kingdom began,’ Habicht said.

Amenhotep’s name meant ‘Amun is satisfied’ – referring to the ancient Egyptian god of the air.

Morares and Habicht’s digital reconstruction offers a first-of-its-kind look at the face of this celebrated king. It was made possible by the Egyptologists who paved the way for this work.

‘This work was not done just by us, but by all those who studied and study ancient Egypt seriously, always sharing information,’ Morares said.