The constituencies of England and Wales where women are most likely to die young can today be revealed.

Blackpool South has the highest premature mortality rate of 484.6 for every 100,000 women, analysis shows.

Although that rate appears low, it is 3.4 times higher than in Wokingham – the area of the country where women have the best chances of avoiding an early grave.

The affluent Berkshire town had a rate of just 141 per 100,000.

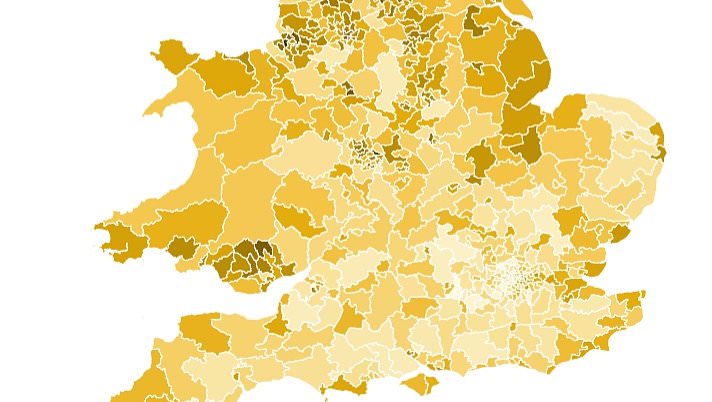

Mortality data held by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), which defines premature deaths as anything before 75 and calculates an age-standardised value, lay bare a clear North-South divide.

Out of the 20 constituencies with the worst premature death rates, 16 of them were in the north and three in the Midlands.

The only one outside the north and midlands was sixth place Blaenau Gwent and Rhymney (407) in Wales.

For comparison, 19 out of 20 areas with the lowest figures were in the south.

Someone is counted as dying prematurely if they die before the age of 75.

Statisticians use age-standardised mortality rates to allow comparison between populations which may contain different proportions of people of different ages.

The rate is usually per 100,000 population.

The only northern location in the best 20 locations was Wetherby and Easingwold (162), located just outside York, which came in 19th place.

World-renowned physician Dr Karol Sikora said that, for women, rates above 350 are unacceptably high.

Only 34 out of the 575 (5.9 per cent) constituencies in England and Wales fell below this mark.

Veena Raleigh, a senior fellow at health charity The King’s Fund, believes more needs to be done to fight health inequality.

She told : ‘Mortality in women in this country has for too long been much higher than it should be.

‘Our female life expectancy is amongst the lowest of all of Western European and other high income countries.

‘In the most deprived areas, between 2010 and the pandemic, life expectancy for women actually fell.

‘This is a story of two halves really, between the more and less deprived areas.

‘Reducing socio-economic inequalities is critically important for reducing these health inequalities, and targeted action is needed to reduce risk factors such as smoking and obesity.

‘It’s great that the Government, introduced the sugar tax a while ago. But we need many more targeted interventions to ensure that food manufacturers, for example, reduce the amount of sugar, salt, and fat in ready-made meals.’

Premature deaths might happen from illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, injuries, violence and even suicide.

The ONS data, which defines a premature death to be anything before 75, does not include Scotland or Northern Ireland.

It is also different to life expectancy, which is typically lower in Scotland due to the well-publicised problems of high alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet, sedentary behaviour and smoking rates (which are slightly higher than England).

Scotland also has the worst drug death rate in Europe, which in 2022 were 2.7 times as high as the rates for England and Northern Ireland, and 2.1 times as high as the 2022 rate in Wales.

Blackpool has also long been plagued with widespread drug and alcohol abuse, mental health crises and high suicide rates.

These types of deaths have been described by the bleakly poetic phrase ‘deaths of despair’ by health researchers.

A study in 2022 revealed that the UK has some of the most extreme regional health inequalities among developed nations.

Think tank The Health Foundation found in a 2020 study that people under 75 living in the poorest tenth of England are around three times more likely to die in the next year than someone of the same age living in the richest tenth.

And analysis by Cancer Research UK has suggested that 33,000 extra cases of cancer in the UK each year are associated with deprivation.

The charity said that these cases, which is nearly one in 10 (9.1 per cent), could be avoided if health inequalities were tackled.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of the extra cases linked to deprivation, mostly because smoking is much more common with those living in deprived areas.

They are also more likely to be overweight or obese, which is the second biggest preventable risk factor for cancer after smoking.

Deprived people are also less aware of cancer symptoms and also experience more barriers to seeking help – such as getting an appointment at a time that works for them.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: ‘These are not just statistics, but real lives cut short, families devastated, and communities suffering.

‘This government inherited a country divided by health inequalities – life chances and life expectancy should not be determined by where you live.

‘Through our Plan for Change, we will tackle this head on and deliver on our commitment to halve the gap in healthy life expectancy between the richest and poorest regions in England.’