The Old Admiralty Building is a Queen Anne-style landmark just off Whitehall which is owned by His Majesty’s Government.

It was formerly the headquarters of the Royal Navy back when Britannia ruled the waves, and today it houses the Department for Business and Trade.

Famed for splendid red-brick walls, Portland stone pillars and copper-topped towers, the historical building sits on a hectare of prime land next to Horse Guards Parade and has been the workplace of icons such as Ian Fleming, in his role as a spy, and Sir Winston Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty.

No fewer than 4,695 civil servants are currently based in the five-storey pile, which was refurbished five years ago at a cost believed to be around £45million.

These lucky men and women enjoy the use of one of Britain’s most stunning offices.

There are views of No 10, St James’s Park and Big Ben, while the state-of-the-art interior combines air-conditioned modernity with a host of period features, including wood-panelled walls, wrought-iron staircases and more than 4,000sqm of marble mosaics.

Or at least they would enjoy the use of Britain’s most stunning office – if they bothered to go there.

But this is the British Civil Service, where the cult of home-working reigns and turning up at HQ has become increasingly optional.

When the Mail visited this week, with the summer holidays in full swing and barely a cloud in the sky, hard-working employees were conspicuous by their absence.

Between 8.45 and 9am on Wednesday, at the height of rush-hour, I counted maybe a few dozen members of staff crunching their way across the gravel of Horse Guards Parade into the building’s southern entrance.

Roughly similar numbers arrived via a doorway on its northern side.

The Mail can reveal that the Department for Business and Trade is, against very stiff opposition, the single worst department at coaxing Sir Humphrey to return to the coal-face.

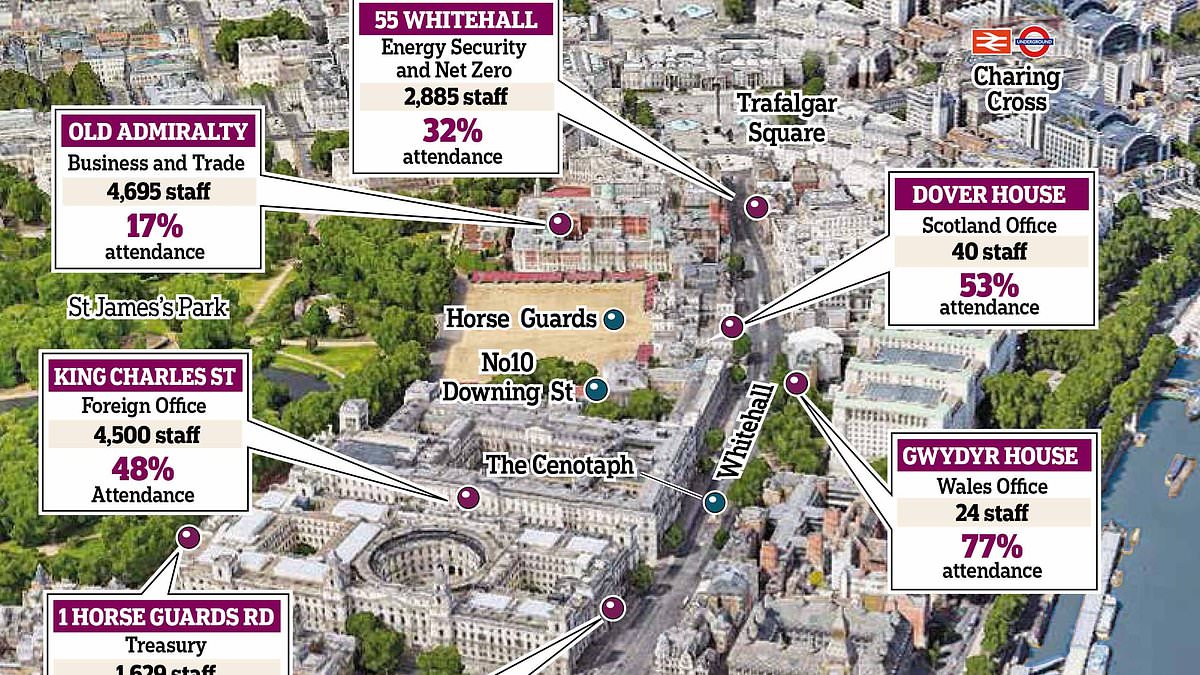

On an average day, a mere 813 of the 4,695 civil servants based at the Old Admiralty Building, or just 17.3 per cent, turn up. That means around five out of six are elsewhere.

We can reveal these striking figures thanks to data unearthed via the Freedom of Information Act by this newspaper over the past month.

This lays bare the extent to which the legacy of Covid continues – some four years after the pandemic – to gum up the engine room of government.

The numbers are scarcely believable: of the 36,613 Whitehall staffers for whom data is available, a mere 12,308 can be found at the office where they are based on a normal weekday.

That equates to 33.6 per cent. Or almost a third.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the departments with the fewest employees going into the office tend to be the worst-performing.

In addition to Business and Trade, which presided over the Post Office Horizon scandal, let us consider the Department for Work and Pensions, where 2,385 HQ staff oversee a benefits system that doles out more than £250billion a year and accounts for over 20 per cent of all government spending.

Based at Caxton House, a post-war concrete building in Victoria, the department has rarely been more inefficient.

A report by the National Audit Office last month found it had ‘fallen short of the expected standards over recent years’, with people telephoning the Work and Pensions helpline forced to spend a combined 750 years on hold in the last tax year.

This winter, it’ll be stripping around 10 million pensioners of their winter fuel payments.

And the civil servants responsible? Our data suggests that the DWP manages to get just 682 of its 2,385 employees into head office on an average day. That’s an attendance rate of a paltry 28.6 per cent.

Take also the catastrophically inept HMRC, a byword for chaos which this week confessed that it’s unlikely to recover an astonishing £19billion in unpaid taxes. Some 850,000 calls to the taxman went unanswered in January alone, and 56,000 customers were cut off automatically from its call centre after being kept on hold for 70 minutes.

The taxman’s headquarters is at 100 Parliament Street, a vast Edwardian building adjacent to Parliament Square. A total of 1,012 employees are supposedly based there. But the Mail can reveal that a mere 303, or 29.9 per cent, cross the threshold on an average day. Sharing the building is the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, whose 975 members of staff eligible to use HQ are currently wrestling with the thorny issue of social media regulation in the wake of the recent riots.

They appear even more averse to setting foot in the building than their chums at HMRC: a mere 224, or 23 per cent, normally attend.

How have these shocking figures been kept hidden until now?

The full extent of Whitehall’s addiction to home working has been concealed from the public thanks to a remarkable sleight of hand performed by senior mandarins as Britain emerged from the Covid pandemic in early 2022.

As the private sector was busy enticing workers back to the office, Whitehall remained a ghost town.

So senior ministers led by Jacob Rees-Mogg, then minister for ‘government efficiency’, told Civil Service chiefs to encourage their employees back in the office.

To monitor the success of this initiative, Rees-Mogg instructed departments to publish data about how many people were returning, which could be assembled into a league table that might shame lackadaisical arms of government into pulling their socks up.

It seemed like a bright idea. But there was a catch.

For in a display of either cunning, obstructiveness or pragmatism (depending on one’s point of view) senior Civil Service mandarins chose not to reveal what percentage of staff were actually turning up in person.

Instead, departments agreed to put out what was called ‘occupancy data’ for HQ buildings.

Weekly figures began to be released in February 2022 and these numbers have since closely followed.

Today, Ed Miliband’s Department for Energy Security and Net Zero claims 100 per cent ‘occupancy’ of offices, while Louise Haigh’s Transport department provides a figure of 82 per cent.

These are encouraging figures. But they are also misleading.

For the advent of so-called ‘hot-desking’ – where workers do not have a specific desk reserved for their use – means that many government offices these days contain far fewer workspaces than the number of employees who work there.

This means that a department that claims to be achieving 70 per cent ‘occupancy’ will often only be managing to get a third of its employees into the HQ building.

Take, for example, the aforementioned Department of Transport, architects of the £25 billion debacle that is HS2.

It claims an ‘occupancy rate’ of 82 per cent for its HQ at Great Minster House, near Lambeth Bridge.

But our figures show that while 2,840 civil servants are based in the building, it contains only 1,261 desks.

It means that for the department to achieve its impressive 82 per cent ‘occupancy rate’, it needs only 1,034 members of staff, just 36.4 per cent, to show up daily.

This misleading system even creates a perverse incentive for Civil Service chiefs to remove desks from their offices, as this would improve the ‘occupancy rate’ without extra employees turning up.

While there is no evidence that this has taken place, one former minister from the last government describes it as ‘a huge loophole waiting to be exploited’.

How has the Mail discovered the Civil Service’s creative accounting over its working from home culture?

In June, the paper filed Freedom of Information requests with all 20 government departments, asking how many members of staff were based at their various HQs and how many desks or workspaces those buildings in fact contained.

We then used the most recent occupancy figures provided by each department to calculate the number of people that were actually in the office – and to find the ‘real’ attendance rate.

A total of 17 departments have so far responded and their answers are carried in the tables here.

The data may help explain the malaise affecting Britain’s public services. According to numbers released by the Office for National Statistics last year, the public sector (where 48 per cent of all staff work partially from home) is now 5.7 per cent less productive than it was before the pandemic, while the private sector (for which the figure is 40 per cent) has experienced a 1.3 per cent uplift.

His Majesty’s Home Office, recently dubbed ‘dysfunctional’ by the government’s ex Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration David Neal, is a case in point.

It was only recently boasting that its Marsham Street HQ, a few blocks south of Westminster Abbey, has an impressive 86 per cent ‘occupancy rate’.

The real state of affairs is subtly different. Our research reveals that the building is home to 4,139 employees, but contains only 2,014 desks.

That suggests that only 1,732 civil servants, or 41.8 per cent of the pay roll, show up there on a normal day – less than half the number that the department would have us believe.

Senior Home Office managers seem powerless to improve the situation, both at HQ and elsewhere.

In a leaked email obtained by The Mail this week, an official told the Immigration Enforcement unit that too many of its staff are failing to comply even with the ‘minimum’ attendance policy of two days a week.

‘The department is completely empty on a Monday and a Friday,’ a source revealed. ‘It’s like a ghost town. And on Tuesday to Thursday only bits are busy.’

Meanwhile the Department for Health and Social Care, which is responsible for around 7 million Britons currently languishing on NHS waiting lists, claims 72 per cent occupancy of its Victoria Street HQ.

We can reveal that the property boasts 2,203 staff but contains a mere 868 desks. So on a normal day we can assume that just 625 people, or 28.4 per cent of the workforce, are to be found there.

The Foreign Office claims occupancy of 71 per cent, but has only 3,027 desks for 4,500 employees, meaning ‘real’ attendance is just 48 per cent, while the Treasury, manages to get just 39.6 per cent of staff to turn up, despite claiming 63 per cent occupancy.

What Chancellor Rachel Reeves, thinks of this is anyone’s guess. Before the election, she said she wanted to see ‘more people in the office, more of the time’ and that turning up to the office is ‘good for productivity and morale’.

Her ambitions seem to have been thwarted, thanks to senior figures on the Left of the party who are in hock to the unions, which vigorously support home working.

They include both Transport’s Ms Haigh and Deputy Prime Minster Angela Rayner, who has told staff she supports so-called ‘flexible working’.

Perhaps as a result, Civil Service job adverts posted in recent days shamelessly ignore a supposed target – introduced by the Conservatives – that required all staff to attend the office at least three days per week.

This week, The Telegraph reported that an opening for a customer service adviser in the DWP said applicants only need to show up twice a week.

Ms Rayner is also in charge of Housing, the ministry that has consistently failed to hit housebuilding targets.

A mere 31.3 per cent of staff turn up each day at the modern HQ on Marsham Street.

They share the building, built at a cost of £311million in the early 2000s, with colleagues from Defra, architects of the Rural Payments Scandal (dubbed ‘frankly embarrassing’ by the Public Accounts Committee), whose staff manage a paltry 34.5 per cent attendance.

It should be stressed that our figures only cover Whitehall HQs, where around 50,000 civil servants work in 20 headquarters buildings.

They don’t show what proportion of the remaining 460,000-odd civil servants in offices across Britain are up to. Its unclear whether attendance is better or worse in the provinces.

So how bad for productivity is working from home?

Academic studies have turned up increasing evidence that it can impact performance and limits career development opportunities, particularly for young or inexperienced employees at the start of their careers, who find it harder to learn first-hand from their superiors.

A 2023 research paper by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to this end found that call-centre workers answered eight per cent fewer calls when working from home.

And a recent study by the Universities of Chicago and Essex found that productivity among 10,000 IT workers decreased by between 8 and 19 per cent when staff worked from home.

‘Uninterrupted work hours shrank considerably.

Employees networked with fewer individuals and business units, both inside and outside the firm,’ it read.

‘They received less coaching and 1:1 meetings with supervisors.’

On the other side of the debate, unions and many middle-managers with suburban homes with ample space to work from, strongly support the practice, with advocates insisting it has no impact on productivity and improves work-life balance.

In a statement, the Cabinet Office, which oversees the Civil Service, argues that the Mail’s figures showing what proportion of HQ staff are in the office ‘do not reflect the fact that while many staff are registered at their department’s HQ, they work from other buildings or are required to make regular visits to operational sites as part of their roles’.

The statement continues: ‘The Government’s entire focus is on the work of delivering change.’

Incidentally, the same Cabinet Office is one of the three Departments who are still refusing to answer the Mail’s Freedom of Information Request seeking to establish how many staff actually work at their HQ.

According to its response to our inquiries, such information (which other ministries were happy to release) should be ‘exempt’ from disclosure under UK law.

They claim that telling us how many civil servants are showing up at HQ would ‘damage national security’, concluding that ‘the balance of public interest favours withholding this information’.

The two other departments that wouldn’t provide figures are the MoD, which claimed the information was ‘not held centrally’ (it remains unclear how they were then able to publish occupancy figures), and the Department for Education, which says its response is ‘delayed’.

Quite how long those explanations hold, or what taxpayers will make of the astonishing argument that there is no ‘public interest’ in knowing whether civil servants attend their hugely expensive offices, it is hard to know.

But there’s every chance that the Labour Government, which recently abandoned Tory plans to reduce Civil Service headcount by 60,000, will support this policy of obfuscation.

To that end, the publication of Whitehall ‘occupancy data’ – which paused in June on the grounds it was too politically sensitive to be released during an election campaign – has still not resumed in the month since Labour took office. No one will say if, or when, it will start up again.

The minister in charge of the Cabinet Office, Starmer loyalist Pat McFadden, is nominally responsible for this ongoing cover-up.

Like many senior members of the Whitehall ‘blob’ he must by now know exactly how many civil servants are still working from home, four years after Covid struck, and how many are dragging themselves into their landmark Whitehall offices. But he doesn’t appear to want taxpayers to find out.