When Karen Pryor first saw the shocking headlines in 2022 about the massacre of four Idaho college students inside their home, her mind instantly went back to a time more than four decades earlier.

‘It made me think about what happened to us – as it just sort of seemed random,’ she tells the Daily Mail in an exclusive interview.

‘I just thought thank God that two [of the students] survived. And please give the families strength.’

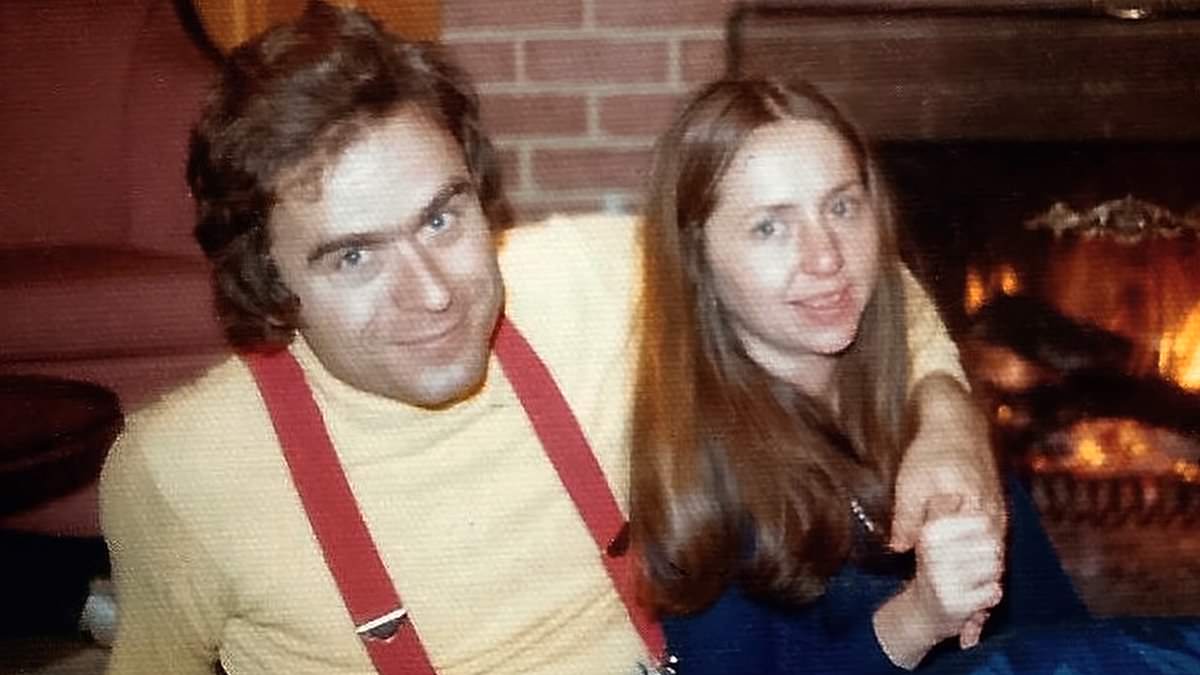

It was around 3am on Sunday, January 15, 1978, when notorious serial-killer Ted Bundy broke into the Chi Omega sorority house at Florida State University in Tallahassee and attacked four students.

The victims, who included Pryor, were all sleeping in their beds, unaware that the depraved murderer had chosen them as his latest prey.

Pryor suffered horrific injuries including a skull fracture and had to undergo multiple rounds of surgery.

Her roommate, Kathy Kleiner, was also seriously injured but survived.

Two of their sorority sisters – Margaret Bowman and Lisa Levy – died after being savagely beaten with firewood and strangled with pantyhose.

A fifth student, Cheryl Thomas, living in a house a few blocks away, was also brutally attacked by Bundy but lived.

It was an unfathomable, violent rampage in a place of carefree innocence and youth that shocked the nation and made headlines across the globe.

And one that has eerie parallels with the chilling crime that unfolded 44 years later, 2,500 miles away in the college town of Moscow, Idaho.

In the early hours of Sunday, November 13, 2022, a group of University of Idaho students had returned to their off-campus home after enjoying their Saturday nights out.

Most of them were in their rooms in bed when a killer broke into 1122 King Road and slaughtered four victims – Kaylee Goncalves, Madison Mogen, Xana Kernodle and Ethan Chapin.

At least some of the victims were also sleeping at the time, defenseless against the attack.

All four had also been part of Greek life at their college.

Goncalves was a member of Alpha Phi, while Kernodle and Mogen were Pi Beta Phi sisters. Chapin, Kernodle’s boyfriend, was part of Sigma Chi – and the young couple had spent their last night together at a party at the frat house.

In both cases, survivors lived to tell the tale. Idaho roommates Dylan Mortensen and Bethany Funke both escaped the slayings.

But there was something else that struck Pryor as being chillingly similar to what she went through back in 1978: The victims didn’t know their killer.

‘When I heard about the case, I thought: I bet this is not somebody they know,’ Pryor tells the Daily Mail.

‘I sort of had a feeling that I bet this is somebody who is just mad at the world or saw somebody that caught his eye walk into that house.’

She adds: ‘The number of people who were attacked, and them being male and female, it made me think, I bet you it’s somebody that just saw this house, saw the girls walk in maybe, and something snapped.’

When Bryan Kohberger was arrested and charged with the murders a month later on December 30, 2022, Pryor’s gut instinct appeared correct.

The accused killer had no known connection to any of the victims found dead inside the home.

Even now, more than two years later – and with the case barreling toward a blockbuster trial in August – Kohberger’s potential links to the four slain students and the alleged motive for the murders remain a mystery.

Bundy also did not know his victims.

He preyed on young women, female college students and teenage girls, kidnapping, raping and murdering them in a campaign of terror that spanned at least seven states.

Days before his execution in 1989 – after spending years professing his innocence – he confessed to at least 30 murders.

Even before Bundy was captured – about a month after the bloody rampage Chi Omega – Pryor says she felt sure the attack was random and that her attacker was someone she did not know.

So much so that, when she left the hospital to continue her recovery at her parents’ home, no part of her feared he might return.

‘I never felt like he was after me,’ Pryor says.

‘There were four girls in the house and one down the street [who he attacked]. I didn’t know who it was but I didn’t feel like he was after a particular person.’

‘I felt like he was after a female body,’ she adds.

The off-campus home where the four University of Idaho students were murdered on November 13, 2022 (seen on November 29, 2022)

While Pryor will likely ‘never get over’ the murders of her two friends, Lisa and Margaret, she insists she has ‘never had survivor’s guilt’ and has never let that night rule her life.

It’s something she hopes, too, for Mortensen and Funke.

Pryor says she imagines they feel some guilt over their response during those fateful hours.

Through court documents, it was revealed that Mortensen, then aged 20, heard some disturbing noises and a man’s voice she did not recognize inside the home at around 4am.

When she opened her bedroom door, she saw a man dressed in all black and wearing a mask walk past her room and head toward the back door.

In a moment of panic, Mortensen and Funke sent each other a flurry of texts and phone calls.

They also desperately called and messaged their four friends inside the home.

No one answered.

Around eight hours would pass from the terrifying encounter before a 911 call was made just before midday – and the horrors inside the home came to light.

The delay in alerting authorities would have made no difference to the victims’ chances of survival, according to Goncalves’ father. He said the coroner informed him that an earlier 911 call would not have saved the victims, who were stabbed multiple times and suffered ‘extensive’ wounds.

Still, Mortensen and Funke have been hounded online with attacks and pointed questions from critics.

‘I’m sure they’ve gone through some really bad times and there is probably guilt there,’ Pryor says.

‘If they had called 911 earlier, though, [the victims still] wouldn’t have lived, so there should be no guilt about trying to save them.’

When Pryor thinks about her own experience, her sorority sisters’ quick actions may have meant the difference between life and death for her and her roommate.

‘A girl saw somebody running out – it was sort of the same thing, he was dressed in dark clothing with a cap over his head, not a mask, so his face showed… and she immediately went upstairs, woke somebody up, said let’s walk around and see if anything is amiss,’ she says.

During that search, the sorority sisters came across Pryor, who had managed to stumble into the hallway seriously injured and covered in blood.

She and her roommate were rushed to hospital for treatment and survived.

Pointing to the case in Idaho, she adds: ‘There has to be a reason why they didn’t reach out or call for help or go and knock on the door.’

Pryor says her ‘heart breaks’ for Mortensen and Funke, and for what the two young women have gone through.

‘I feel sorry for them. I know they lost friends,’ she says.

‘My heart breaks for that.’

The two surviving roommates are expected to be key witnesses at Kohberger’s trial this summer, where he is facing the death penalty.

For Pryor, who testified at Bundy’s trial, her attacker’s execution in 1989 finally gave her some ‘closure.’.

‘People talk about closure and ask victims’ families if they have closure and they’ll say ‘well no, because our loved one is still dead,’ she says.

‘I don’t think that’s what closure means. I think closure is, even if you don’t get the outcome you want, it’s at some point you close the book and say I’ve got to live with the consequences and go on. And I’ve got to live with the memory and honor them.

‘So for me, his execution was my closure.’

Pryor ended up moving back into the Chi Omega sorority house and finishing her studies at Florida State University.

She never once saw a counselor or psychiatrist to help her deal with the traumatic experience of that night in 1978.

For her, talking with friends and family about what happened has helped over the years.

‘When I talk about it, it’s almost like you hand a little bit of the grief over,’ she says.

‘Every time you talk about it, it’s a little easier to talk about.’

Now a happily married mother-of-two and grandmother living in Atlanta, Pryor urges other survivors to open up what they have gone through – and to seek medical and professional help if they need it.

But her most poignant message to fellow survivors is to not let the experience – or the person who attacked them – have any power over their lives.

‘Just remember: you’re in control of your life,’ she says.

‘My advice is that the best you can do is put one foot in front of the other and move on.’