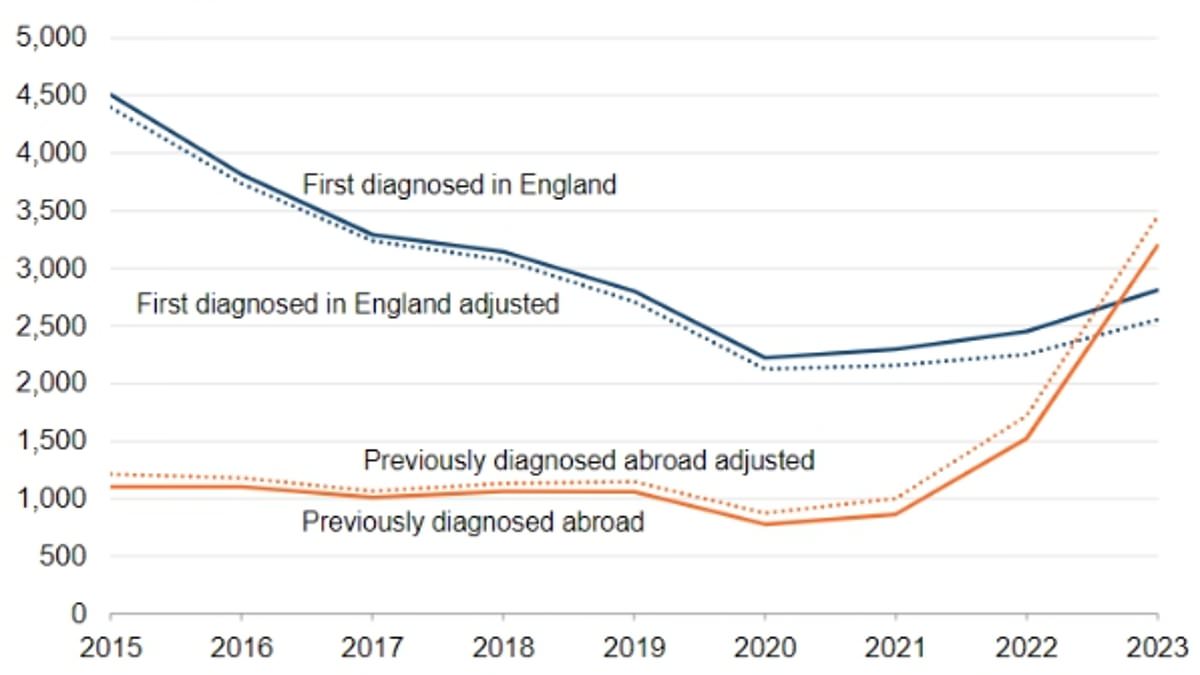

A rise in HIV diagnoses to hit a 15-year high is partly due to an increase of cases among migrants coming to England, an official report has found.

A total of 6,008 new HIV cases were recorded last year, including those previously diagnosed abroad – an increase of 51 per cent.

For the first time, over half of all HIV diagnoses were made among those previously diagnosed abroad, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) found.

Around 53 per cent of cases (3,198) were diagnosed overseas, with half these cases among people born in Eastern Africa, and 22 per cent from other parts of the continent.

A further eight per cent each gave their place of birth as Asia, Latin America or the Caribbean.

Another 253 people were first diagnosed in England within two years of arriving in the country after being born abroad.

Most people were rapidly linked to care shortly after their England arrival, officials found.

In its annual report on the disease, the UKHSA said: ‘The rise in HIV testing together with a higher and sustained positivity in black African heterosexuals may be suggestive of ongoing transmission.

‘However, this number could also be affected by changing patterns of migration with a recent rise in people diagnosed with HIV abroad arriving in England.’

Net migration stood at 685,000 last year, a slight reduction from the previous high of 764,000 in 2022. Out of the 1.16 million work and study visas granted to migrants in the past year, 263,000 were given to people from Africa.

Elsewhere in its report, the UKHSA revealed that HIV diagnoses had soared by 30 per cent in heterosexual people over the year — more than triple the rise seen in those within the LGBTQ community.

Heterosexual men had the biggest increase in new HIV diagnoses over the last year with over 600 cases in 2023, a rise of 36 per cent.

Heterosexual women saw a small but still significant rise with nearly 800 new cases, a rise of 30 per cent on the previous year.

Charities said the rise in cases left the Government’s goal to end new HIV transmissions in England by 2030 ‘in jeopardy’.

The data shows the majority of new cases involve patients of ethnic minority groups.

Sexual health charity Terrence Higgins Trust said the goal of ending new cases by 2030 is ‘in jeopardy’.

HIV damages the cells in the immune system and weakens the body’s ability to fight every day infections and disease.

The virus is spread through the bodily fluids — such as semen, vaginal and anal fluids, blood and breast milk — of an infected person. However, it cannot be spread through sweat, saliva or urine.

It is most commonly transmitted through having condom-less anal or vaginal sex.

Tests are the only way to detect HIV. They are available from GPs, sexual health clinics, some charities and online and involve taking a sample of saliva or blood.

A preventative HIV medication, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), can also be prescribed to over-16s. It slashes the risk of contracting HIV, if it is taken correctly.

Those who take post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) — an anti-HIV medicine — within 72 hours of exposure may avoid becoming infected at all.

For those who are infected, no cure is available for HIV.

But antiretroviral therapy (ART) — which stops the virus replicating in the body, allowing the immune system to repair itself — enable most to live a healthy life.

Chief executive Richard Angell said: ‘The new figures show people from ethnic minorities face an increasing burden of HIV, with rising diagnoses and worse health outcomes than the population as a whole.

‘Recent strong progress among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men seems to have stalled.

‘And, almost across the board, the picture is worse for those living outside of London, where resources are most limited.

‘Today’s figures are a call to action: we need innovation and new resources to address these health inequalities and reach the 2030 goal. Time is of the essence.’

Dr Tamara Djuretic, co-head of HIV at the UKHSA, said: ‘It is clear that more action is needed to curb new HIV transmissions, particularly among heterosexuals and ethnic minority groups.

‘Addressing these widening inequalities, ramping up testing, improving access to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) and getting people started on HIV treatment earlier will all be crucial to achieving this.

‘HIV can affect anyone, no matter your gender or sexual orientation, so please get regularly tested and use condoms to protect you and your partners’ health.

‘An HIV test is free and provides access to HIV PrEP if needed. If you do test positive, treatment is so effective that you can expect to live a long, healthy life and you won’t pass HIV on to partners.’

HIV damages the cells in the immune system and weakens the body’s ability to fight every day infections and disease.

The virus is spread through bodily fluids — such as semen, vaginal, blood and breast milk — of an infected person. However, it cannot be spread through sweat, saliva or urine.

It is most commonly transmitted through having unprotected anal or vaginal sex.

Tests are the only way to detect HIV. They are available from GPs, sexual health clinics, some charities and online and involve taking a sample of saliva or blood.

PrEP, a preventive HIV medication, can also be prescribed to over-16s. It slashes the risk of contracting HIV, if it is taken correctly.

Those who take post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) — an anti-HIV medicine — within 72 hours of exposure may avoid becoming infected at all.

For those who are infected, no cure is available for HIV.

But antiretroviral therapy (ART) — which stops the virus replicating in the body, allowing the immune system to repair itself — enable most to live a healthy life.

Levels of the virus in those taking ART will drop so low that they can have condom-less sex without passing HIV on to their partner — though this can take up to six months.

AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) is the name used to describe an array of potentially life-threatening infections and illnesses that happen when your immune system has been severely damaged by HIV.

However, those who are diagnosed with HIV early and begin treatment will not develop any AIDS-related illnesses and will live a near-normal lifespan.

Public health minister Andrew Gwynne said: ‘This data shows we have much more work to do and brings to light concerning inequalities in access to tests and treatments.

‘I will be working across government to ensure that we work to stop HIV transmissions for good. Our new HIV Action Plan aims to end transmissions in England by 2030 with better prevention, testing and treatment.’