A more dreadful sight I never saw,’ uttered PC Edward Watkins, still reeling from the shock.

A few hours earlier, at 1.44am on September 30, 1888, the officer on his beat in London’s East End had turned on to Mitre Square and stumbled upon a corpse so mutilated that, as he later told reporters, ‘it was difficult to discern the injuries to the face for the quantity of blood which covered it’.

The Whitechapel Murders were truly most foul. Each of the five female victims was savagely disfigured and her blood left to spill across the cobbles of Victorian London.

But perhaps the most terrifying aspect of this quintuple homicide, committed over less than four months, is that for over a century, the killer’s identity was a mystery. Instead, he simply became known as Jack the Ripper.

And then, ten years ago in 2014, the Mail exclusively revealed how amateur sleuth Russell Edwards had identified one Aaron Kosminski, a Jewish immigrant from Poland, as the fabled killer.

The evidence was as overwhelming as it was stomach-churning.

A decade on and the Mail can now reveal further astonishing evidence as to how Kosminski’s hitherto-unknown ties to the highly secretive Freemasons motivated his sadistic killings – and how his Masonic connections shielded him from law enforcement, despite widespread conviction within the police that Kosminski was indeed the murderous Ripper.

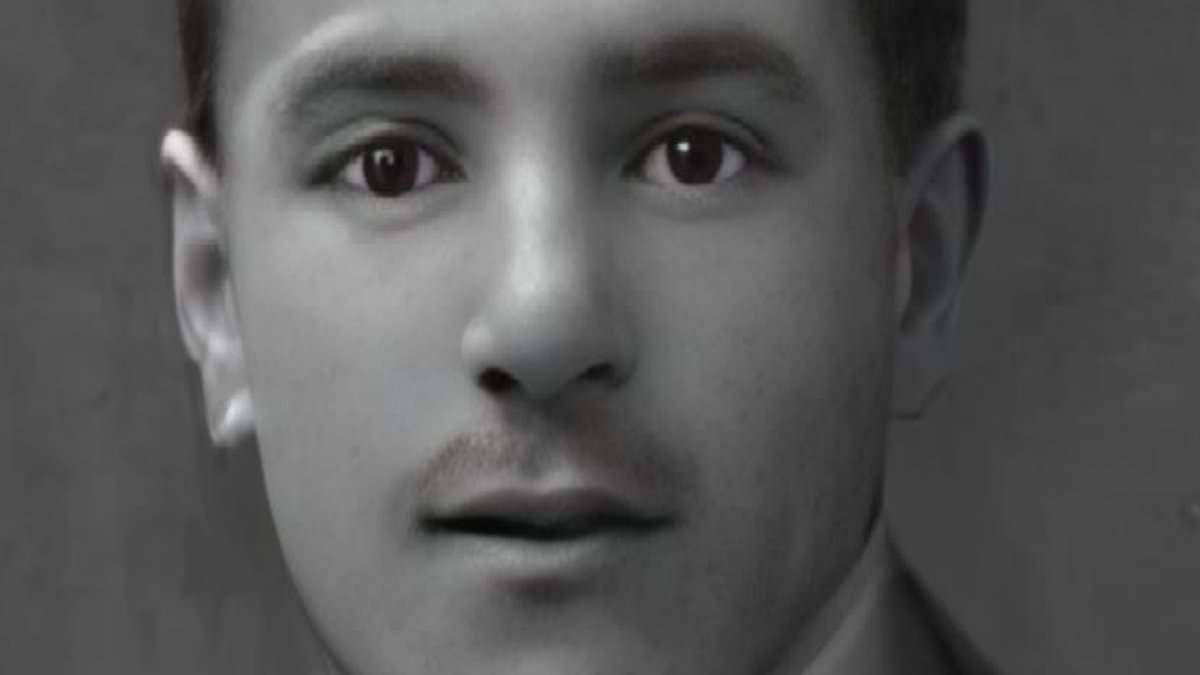

Not only that but, thanks to cutting-edge technology, Edwards has created an astonishingly detailed photograph of the most notorious serial killer in British history.

After 136 years, the latest book from Russell Edwards has exposed the conspiracy of silence that shielded Kosminski. And now, the cold case that has chilled the British public for a century can finally be put to rest.

The story of the Ripper’s unmasking began on that morning in late September 1888, when PC Watkins came across the bloodied corpse of Catherine Eddowes, twitching on the pavement in the south-west corner of Mitre Square.

Even for a world-weary copper like Watkins, the cadaver was a horrible sight. Eddowes’s top had been pulled above her chest, exposing a cut from the pit of her stomach up to her breast. Her entrails had been ripped out and left dangling around her neck. Her head was nearly severed from her body and her nose had been dismembered from her face.

Catherine Eddowes was the Ripper’s second victim that night and fourth overall. In total, the Ripper is thought to have claimed at least five lives – the Whitechapel Murders – though some argue the true body count is closer to 11.

However, little could the Ripper have known as the sun came up over London that autumn morning, that he had left at the crime scene a crucial piece of evidence, one that would lead to his eventual outing more than a century later.

In 2007, Russell Edwards – a businessman from North London and Ripper enthusiast – stumbled across a shawl at an auction in Bury St Edmunds alleging to have been found on Catherine Eddowes’s corpse.

Edwards was wary. How on earth could a silk shawl have survived the past century without being cleaned or – indeed – incinerated? Before the advent of DNA profiling in 1984, blood-splattered clothing was rarely kept as evidence, but rather burnt to prevent disease.

But this shawl was fully intact and even marked with what appeared to be blood and semen stains.

Edwards enquired further before purchasing the shawl and discovered that, as Catherine Eddowes’s body was being carted to the morgue on that chilly morning in 1888, Acting Police Sergeant Amos Simpson spotted the shawl and – it being made of fine silk – took it as a gift for his wife, Jane.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Jane was more than a little perturbed when she noticed the blemishes and declined her husband’s well-intentioned gift. Nevertheless, it remained in the family until eventually finding its way to auction courtesy of Sergeant Simpson’s great-great-nephew David Melville-Hayes in 2007.

But while the provenance appeared legitimate, Edwards remained bemused as to how a shawl made of silk and ornately decorated with flowers could have been owned by Eddowes, a destitute drunk who paid for the bottle by selling her body.

The detailing and dyes used to pattern the fabric were adjudged by an expert to be reminiscent of those manufactured in St Petersburg in the 19th century. Edwards had an inkling that perhaps the shawl actually belonged to Aaron Kosminski, a longtime Ripper suspect who had emigrated from the Russian Empire. The pieces were falling into place.

Edwards set to work examining the shawl for DNA alongside a crack team of forensic scientists. It wasn’t long before Edwards had a positive match between the DNA in the blood stains and a direct descendant of the murdered Catherine Eddowes. In other words, the shawl was genuine.

Incredibly, Edwards’s team was also able to identify the DNA found in the semen as Aaron Kosminski’s. They did so by ingeniously matching it to the DNA of one of Aaron’s sister’s descendants, known only as ‘M,’ after requests to exhume Kosminski’s body were rebuffed.

Over the years some remarkable names had been mooted as the man behind the Ripper mask, including everyone from Queen Victoria’s grandson to beloved children’s author Lewis Carroll. But finally, the truth was out.

Edwards, through sheer determination – and a slice of luck – had successfully solved the greatest mystery in British criminal history.

So who was Aaron Kosminski? Born on September 11, 1865, Kosminski grew up in Klodawa, near Warsaw, the youngest of seven children. When he was just eight years old his father died, leaving his then 54-year-old mother to raise him. She remarried, but records suggest the young Aaron may have suffered sexual abuse by his stepfather.

In 1882, the family fled to London to escape the anti-Semitism that had been unleashed across eastern Europe following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. And it was here, in London’s East End, that the young Kosminski would become a cold-blooded killer.

At the time of the Ripper murders, the head of the London Criminal Investigation Department, Dr Robert Anderson, already suspected Kosminski to be the perpetrator.

Confidential police reports – published in 1894 as the so-called Macnaghten Memorandum – revealed police believed Kosminksi to have a ‘great hatred of women, specially of the prostitute class, and had strong homicidal tendencies’.

However, police were wary of accusing a Jew. After all, they had no hard evidence and in the climate of the day, knew they’d be met with accusations of anti-Semitism from the East End’s vocal Jewish population.

Luckily for the authorities, however, they never had to arrest the man they suspected of being the Ripper.

In 1890, Kosminski suffered a suspected schizophrenic breakdown – threatening his own sister with a knife – and was committed to Colney Hatch lunatic asylum in North London the following year. Kosminski died 28 years later in the Leavesden Asylum, Hertfordshire. At the time of his death, he weighed just under 7st.

But despite having successfully proven Kosminski’s guilt, Russell Edwards felt there were still questions left to answer. When he started looking into the Ripper murders, he was in his 30s. He’s now almost 60.

But over that time, there was one question which had forever gnawed away at him: just why were the Ripper killings so grotesque? Why does a murderer go to the trouble of mutilating his victims? Could it be a perverted sexual fetish; or, perhaps, was this a manifestation of the suspected schizophrenia for which Kosminski was eventually locked up in an asylum?

In February 2023 a series of photographs landed in Edwards’ inbox. One in particular caught his eye. It looked like a class photo, 15 men – all dressed identically in suits with a flowing overgarment and remarkable handlebar moustaches – staring straight at the camera. These were all members of the Lodge of Israel, an order of Freemasonry set up for Jewish immigrants in Britain.

And among the group of men was none other than Kosminski’s eldest brother, Isaac, a wealthy tailor who moved to London in April 1870 before changing his name to Abrahams.

But what could this have to do with murders committed by Aaron Kosminksi?

In the ancient Masonic Code, the allegorical figure of the ’Master Mason’, Hiram Abiff, was murdered by three assassins known as ‘The Juwes’ for refusing to give up his secrets.

This fable led to the creation of three Masonic ‘blood oaths’ today, which each give graphic depictions of bodily mutilations. The first oath includes the phrase: ‘O that my throat had been cut across, my tongue torn out . . .’ The second proclaims: ‘That my left breast had been torn open and my heart and vitals taken…’ And the third: ‘That my body had been severed in two…’

Comparing these oaths to the Whitechapel Murders, Russell Edwards deduced that Jack the Ripper was not randomly mutilating his victims, but carefully carrying out the instructions set out in these Masonic Oaths.

But the role of the Freemasons doesn’t stop there. Edwards acknowledges in his new book that there ‘has always been a nod, or reference to a cover-up by the masons’ to protect Kosminski.

However, his discovery of the photographs confirms it. Aaron Kosminski’s connection to the Israel Lodge of Freemasons explains why he was locked away in an asylum rather than arrested and publicly prosecuted.

The Jewish Freemasons wanted to avoid scrutiny and prevent a groundswell of anti-Semitism. So they covered up the Ripper’s crimes and created a mystery it would take more than a century to unfurl.

After more than two decades of painstaking research, Russell Edwards has provided some belated justice.

Edwards took his evidence to the Attorney General hoping to be granted a second inquest into the Whitechapel Murders. Unfortunately, his request was rejected.

However, in lieu of a fresh inquest, barrister Dr Tim Sampson has his own definitive concluding remarks to this astonishing case: ‘Had the newly available DNA analysis of blood and semen samples obtained from a shawl… been available to the police at that time, it would have been justifiable for the coroner to charge and then seek to have Mr Aaron Kosminski prosecuted for both the murder of Ms Eddowes and the other four known victims of the so-called ‘Ripper’ murders.’

But there was still one final piece of the jigsaw to complete. With no known photographic evidence of Aaron Kosminksi, what did this sordid murderer look like?

Russell Edwards contacted Kosminski’s descendants and received back a plethora of family photographs. Through the use of ground-breaking facial remodelling technology, Edwards was able to process these pictures and create a definitive composite of Jack the Ripper.

It’s an eerie headshot of a young man with high cheek bones, pinned ears, a close crop and a piercing stare. After 136 years, we can now look into the eyes of the most notorious serial killer in British history – Aaron Kosminski, the murderer formerly known as Jack the Ripper.

Naming Jack The Ripper: The Definitive Reveal by Russell Edwards is published by Rowman & Littlefield