Concealed behind the high walls of a brick building in northeastern China, the horrors that went on in the Japanese Imperial army’s Unit 731 remained a secret to the outside world for decades.

Codenamed the Kwantung Army’s Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department, the facility was in fact a Japanese war camp that thousands of prisoners entered, but never left.

Inside, sadistic human experiments beyond most people’s comprehension were carried out on inmates – treated as human guinea pigs for some of history’s most depraved war crimes.

Innocent men, women and children were killed in the most savage ways imaginable – dissected alive, infected with deadly viruses, raped and used for target practice with flamethrowers and even ‘plague bombs’.

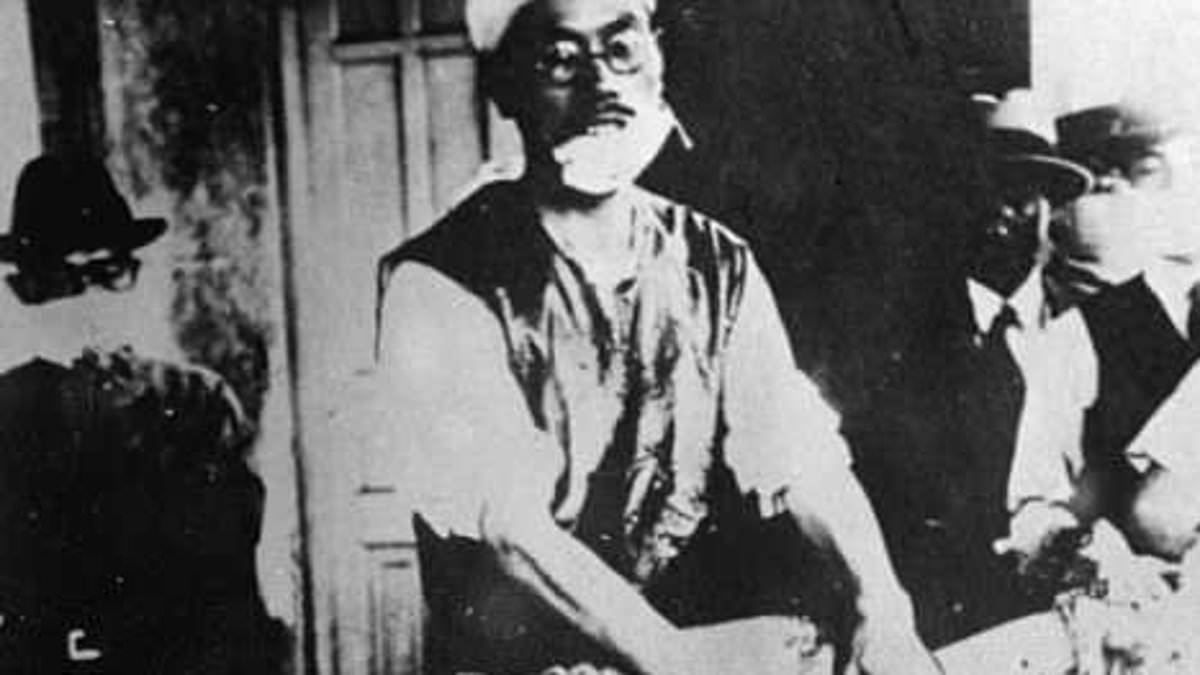

Overseeing all of these unspeakable crimes was Unit 731’s Dr Death – Shiro Ishii – a charismatic surgeon and ultra-nationalist fanatic who is considered the architect of the now notorious death camp’s atrocities.

The army surgeon Ishii established the biological warfare research unit in 1936 to conduct research into germ warfare, weapons capabilities and the limits of the human body.

He did so with significant government funds and the blessing of Emperor Hirohito, who approved the policies and methods set out to him, some of which his brother witnessed first-hand.

Ishii arrived in Manchuria, modern-day China, not long after the occupation forces, and set to work building his empire of death.

A town called Ping Fan, 15 miles south of the regional capital Harbin, was selected as the site for Unit 731 – a far bigger and more secure site than previous camps which had been shut down after their secrecy was compromised.

In the surrounding town, the Japanese occupiers would not permit the construction of buildings high enough to glimpse the violence going on within the compound walls.

‘None of the people around here had any idea what the real purpose of the facility was,’ researcher Han Xiao said. ‘It was the secret of all secrets – trains could only pass with their curtains drawn; the Air Force would shoot down any plane that came too close.’

Once set up, military police began to hunt down victims for the unit’s experiments – many of whom were Chinese civilians including children. The army also sent Russian, British and American POWs there.

The inmates were deliberately kept healthy, fed on a diet of rice, meat, fish and even alcohol on occasion, so their bodies would be in good condition for the experiments to begin.

When one Imperial army general inspected the unit, supposedly set up to help Japan’s war effort, he shared his disgust at its activities, writing about what he saw.

‘It was said that it was for national defence purposes, but the experiments were performed with appalling brutality and the dead were burned in high-voltage electric furnaces, leaving no trace,’ he wrote in his memoir.

The level of dehumanisation was such that the victims were called ‘marutas’ by their captors – Japanese for wooden logs.

Also named the Togo Unit, after Ishii’s favourite war hero whose name he adopted as an alias, the facility acted as a factory for his morbid fantasies.

He and his staff employed gruesome tactics to secure specimens of certain organs for their experiments, according to historian Sheldon H Harris.

‘If Ishii or one of his co-workers wished to do research on the human brain, then they would order the guards to find them a useful sample,’ he wrote in his book Factories of Death.

‘A prisoner would be taken from his cell. Guards would hold him while another guard would smash the victim’s head open with an ax. His brain would be extracted and rushed immediately to the laboratory.

‘The body would then be whisked off to the pathologist, and then to the crematorium for the usual disposal.’

Vivisections were common practice, with former workers revealing what they saw – and even did themselves – decades later.

A former medical assistant at Unit 731, a farmer in his 70s who wanted to remain anonymous, told the New York Times in 1995 about the first time he cut open a live man.

‘The fellow knew that it was over for him, and so he didn’t struggle when they led him into the room and tied him down,’ he said. ‘But when I picked up the scalpel, that’s when he began screaming.

‘I cut him open from the chest to the stomach, and he screamed terribly, and his face was all twisted in agony. He made this unimaginable sound, he was screaming so horribly. But then finally he stopped.

‘This was all in a day’s work for the surgeons, but it really left an impression on me because it was my first time.’

Inmates also had limbs amputated and organs removed before the depraved surgeons reattached their body parts – often in the wrong place – to see the effects.

Germ warfare experiments were also a key part of Unit 731, with Ishii and his henchmen breeding lethal strains of viruses to wipe out the Chinese population.

Enough germs were created to kill everyone on earth many times over, according to reports, with 300 kilos of plague bacteria were produced every month, 500 kilos of anthrax, and nearly a tonne of dysentery and cholera.

Children were fed chocolates laced with anthrax and biscuits infected with plague, while older inmates were given typhoid-infected dumplings and drinks.

Thirty teenagers from Harbin died after being given typhoid-contaminated lemonade, according to a report in the Sydney Morning Herald looking back at the horrors of what it called ‘Asia’s Auschwitz’.

Another atrocity saw men infected with syphilis and then forced to rape other inmates, with the stated purpose of the torture to see how the disease was transmitted.

Women were forcibly impregnated for them and their babies to be used in these experiments.

While babies were born in Unit 731, all of the hundreds of prisoners who were alive when Japan surrendered at the end of the war were murdered and buried as the imperial army tried to cover up its crimes.

Former commanders, who were sworn to secrecy, recognised the savagery of their own operations, but many said they felt numb to them as they carried them out.

Sakaki Hayao, who headed Unit 731’s Lin Kou branch, detailed an ‘extremely cruel’ experiment conducted at the Anda field in his testimony to the Shenyang special military tribunal in 1956.

Hayao said he saw people tied to wooden poles and exposed to anthrax through bombs filled with the bacteria that were dropped from aircraft or detonated at close range.

The cruel experiment was conducted just a few months before Japan’s surrender. ‘It was an especially brutal act,’ he said.

Three days after the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, soldiers were ordered to bury the burnt bones of murdered inmates in an effort to conceal the unit’s crimes.

Soviet forces invaded the former Manchuria in August, and Unit 731’s staff retreated back to Japan, with many never revealing their crimes and going on to enjoy relatively normal lives.

One of the most disturbing elements is the consequences many of these horrific experiments – unique in scientific history – had for medical knowledge today.

Some of the experimental data gleaned from the human test subjects marked advances in modern medical understanding.

Ishii was said to be particularly proud of Unit 731’s discoveries about the mechanism of frostbite.

These were made by tying people to posts in temperatures 20 degrees below zero, as well as submerging their limbs in freezing water.

The effects of various remedies were tested on their frostbitten limbs, which were also painfully heated up by the sick surgeons as they tested the effects on victims as young as three.

General Okamura, a friend of Ishii, proudly noted in his memoirs ‘I did not know the details of the medical advances he made, but after the war Ishii told me that his work produced more than 200 patents.’

When the extent of what happened there was finally unearthed, the Americans helped to cover up the program in exchange for some of its data.

The vale drawn over his crimes meant that despite all the pain and death he inflicted and oversaw, Ishii was allowed to live out his days peacefully – dying from throat cancer in 1959.