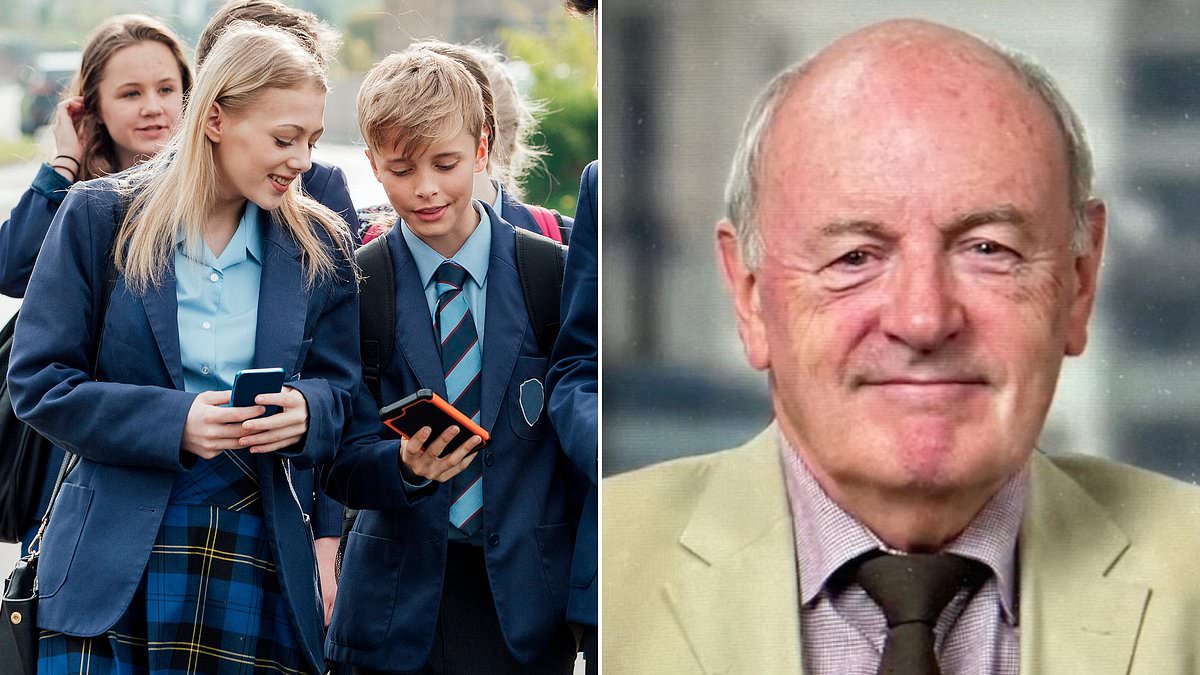

Gifted pupils are being increasingly ignored by Scottish schools, it’s claimed.

The number of children receiving extra help in the classroom due to dyslexia, autism and mental health problems has soared by 58 per cent since the pandemic.

Meanwhile, those getting additional work to keep them stretched and challenged has slumped by 17 per cent.

The revelation comes as ministers are facing pressure to make education reforms, as standards of reading, writing and maths are falling away amid growing violence, ill-discipline and absenteeism.

Last night, Chris McGovern, chairman of the Campaign for Real Education, said: ‘This neglect of the most able children – whether with academic or practical skills – is potentially disastrous.

‘So-called inclusive education should mean catering for different abilities and getting the maximum from them all.’

He added: ‘Not being taught in line with your ability can be extremely frustrating for children and affect their mental health.

‘Bad behaviour in the classroom can often be because some of the brightest pupils are bored.’

In 2007, only 1 per cent of pupils had additional support needs (ASN); that figure now stands at 40 per cent.

The rate of increase has accelerated since the first Covid-19 lockdown, which saw schools shut for five months.

Those designated with autism disorders has soared 69 per cent from 21,820 in 2020 to 36,773, according to new Scottish Government figures.

Incidence of dyslexia has risen 46 per cent from 24,132 to 35,245.

And 12,707 pupils are now being supported for mental health problems, up 69 per cent from 7,524.

However, amid the rising tide of diagnoses, those with exceptional academic ability are seemingly being sidelined.

Schools have a legal duty to provide additional support without which a pupil would be unable to develop their ‘talents and…abilities…to their fullest potential’.

But since lockdown, those identified as “more able” and receiving extra help dropped 17 per cent from 3,493 to 2,896.

Steve Ramsden, chief executive of Potential Plus UK, a charity devoted to helping schools and parents teach high-ability children, said: ‘There is a tendency to assign a low priority to “more able” pupils.

‘There is no focus on how to identify or teach these children in teacher training.

‘Failure to provide an appropriate education for “more able” pupils can lead to a miserable school life and lifelong feelings of failure.

‘It can lead to disengagement from learning; poor socialisation, self-image and self-esteem; perfectionism; lack of resilience and a failure to fulfil their potential.

‘These are pupils the education system have failed. For wider society, what a loss this adds up to in terms of people who would have been able to make a valuable contribution but end up with their potential wasted.’

A Scottish Government spokesman said: ‘All children and young people should receive support to reach their full potential and not face barriers to their learning.

‘All teachers undertake ASN training, which is a requirement for registration with the General Teaching Council of Scotland.

‘Our inclusive approach to education across Scotland means additional support needs are being increasingly recognised by local councils, which carry the statutory responsibility for schools.

‘However, we recognise the growth in ASN presents challenges, and that’s why we are deliver-ing a package of £28 million to employ more specialist staff and teachers to support ASN in schools and a further £1 million to help recruit and train more.’