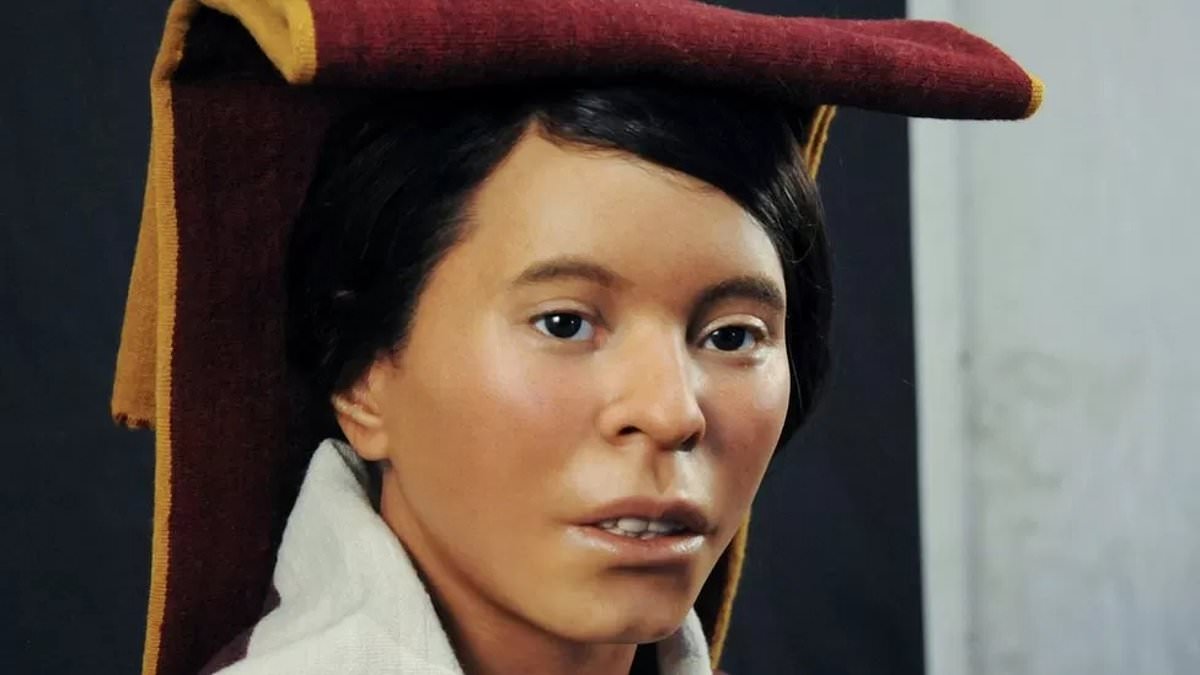

The face of Peru’s most famous mummy, a teenage girl sacrificed in a ritual, has been seen again for the first time in more than 500 years.

Archaeologists unveiled the facial reconstruction of the girl known as ‘Juanita’ or ‘Inca Ice Maiden’ on Tuesday, which was created using body scans, skull measurements and DNA studies – all of which took 400 hours to complete.

Juanita was killed by blunt trauma between 1440 and 1480 on the Argentinian volcano Llullaillaco, 22,100 feet above sea level, leaving her body frozen in time until it was discovered in 1995.

Her preserved, lifeless body was the first evidence that the Incas also sacrificed women in ceremonial processes.

Archaeologists unveiled the facial reconstruction of the girl known as ‘Juanita’ or ‘Inca Ice Maiden’ on Tuesday, which was created using body scans, skull measurements and DNA studies – all of which took 400 hours to complete

Johan Reinhard, the US anthropologist who found the mummy, said: ‘I thought I´d never know what her face looked like when she was alive.’

Reinhard found Juanita wrapped in burial tapestries that were once bright colors but had since turned black due to weathering.

The facial reconstruction was achieved by a team of Polish and Peruvian scientists who worked with a Swedish sculptor, Oscar Nilsson.

The reconstruction now on display at the Catholic University of Santa Maria in Arequipa shows her mouth slightly open and dark, piercing eyes gazing into the distance.

The silicon statue includes colorful attire, head covering, and adornments, similarly based on the mummy scans.

Ruling over a massive swath of western South America along the Pacific coast and Andean highlands, the Inca saw their rich and powerful empire fall to Spanish invaders in 1532.

But some time before, the girl – about 14 or 15 years old – was sacrificed by a blow to the head, possibly in a ritual ceremony that sought divine relief from natural disasters, according to the scientists.

Juanita was killed by blunt trauma between 1440 and 1480 on the Argentinian volcano Llullaillaco, 22,100 feet above sea level, leaving her body frozen in time until it was discovered in 1995

Johan Reinhard (pictured), the US anthropologist who found the mummy in 1995, said: ‘I thought I´d never know what her face looked like when she was alive.

She was found with her hands resting on her lap and her head falling forward.

According to anthropological studies, Juanita was about five feet and four inches tall and weighed just 77 pounds.

Experts believe she only consumed alcohol and drugs in the days leading up to her final breath.

It is thought that the Incas chose the children for their beauty and sacrificed them in a ceremony called a capacocha.

Children were not offered to feed or appease the gods but, instead, ‘to enter the realm of the gods and live in paradise with them.

The facial reconstruction was achieved by a team of Polish and Peruvian scientists who worked with a Swedish sculptor, Oscar Nilsson

It was considered a great honor, a transition to a better life from which they would be expected to remain in contact with the community through shamans.

Reinhard discovered the remains of two other children with Juanita.

The three children’s journey to the place of their death would have begun some 500 miles north of where they were found, in Cuzco, in what is now Peru.

They would then have set off by foot in a long procession with other children, priests and officials, arriving at the foot of the Llullaillaco some weeks later.

Given alcohol made from fermented corn to drink and coca leaves to chew to ward off fatigue and pain, they must have been marched steadily uphill into the thinning air.

They would have had a desperately hard time of it: above 16,000 feet, the body struggles to adapt itself to altitude, and as well as oxygen deprivation, their tiny bodies would have had to cope with painfully low temperatures.

Once they reached the summit, cold and exhausted and dressed in their finest clothes – in the case of the elder girl, a grey shawl adorned with bone and metal ornaments – the children were allowed to die from exposure.

‘The priests lit fires or burned offerings as they waited for the children to fall slowly unconscious, and they were ready to place in their tombs,’ Constanza Ceruti, the Argentinian anthropologist, told the New Scientist magazine.

The three children have been stored in a freezer at the museum. The elder girl is now on display in a specially built case that keeps her remains at -4F, surrounded by a particular gas to prevent deterioration and in a pressurized atmosphere to guard against ice burn.