It was 2am when the door knock came. As a 32-year-old anthropology postgrad student at Roehampton University, I was living alone in a rented studio flat, still up working on my dissertation. Normally I wouldn’t open the door so late but something told me this was important. As soon as I saw it was the police, I knew someone had died.

They told me my dad’s body had been discovered by his cleaner in his Bedfordshire cottage. My friendly pet rat Mr Cuddles heard the voices and popped out to say hello while I babbled that I wasn’t meant to have pets. The officer reassured me it wasn’t his job to police whether people were abiding by the terms of their rental contracts.

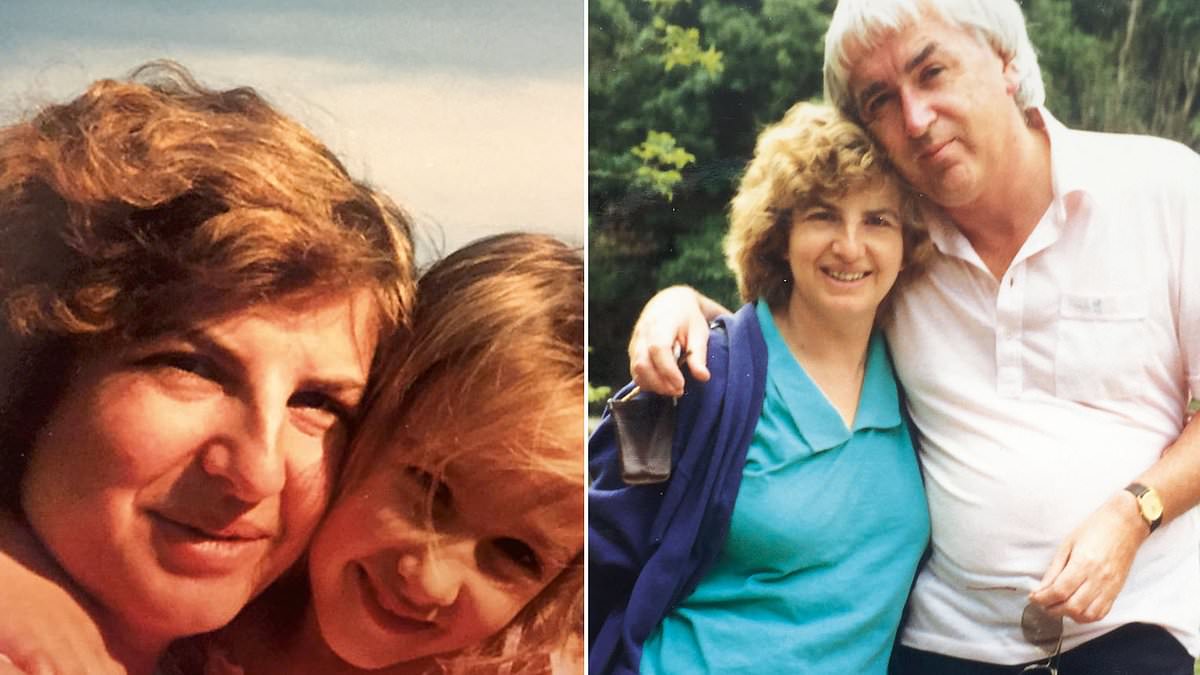

The three of us, London 1981

A few days later the coroner phoned me with the autopsy results: my father, 69, had died of a massive aneurysm. He’d had a few problems for a while – he was diabetic and had undergone a heart bypass a few years earlier. But he was otherwise healthy and working full-time as an IT consultant. His death was a huge and unexpected blow.

My father was an award-winning amateur musician, a Cambridge maths alumnus and a successful businessman. He even moonlighted as a church organist. He had a good life, and he had a good death: painless, and without prolonged illness or suffering. He finished work, sat in his armchair and just dropped dead. I think he died satisfied he’d accomplished all he had set out to achieve in life. His death was sad, but it was a tidy death.

Dad in the mid-90s; Mum at home in North London, 1981

His house was immaculate. Everything I needed was in a folder marked ‘death’ on a shelf. He’d included a copy of his will, his birth certificate, even all his insurance policies. I didn’t have to do anything except grieve.

This wasn’t the first time I’d lost a loved one. My grandfathers both died when I was young, my paternal grandmother before I was born. I grew up an only child, with my parents Roy and Lyn, maternal grandmother Edie and beloved Aunt Jean, who died at 60 after routine surgery. I was in my early 20s and it was my first major bereavement. My grandmother passed a few years later, aged nearly 90.

But when my dad died in 2013 I was the first of all my friends to lose a parent. I became aware of their relationships with their own parents. As the years went by, my friends started dealing with the problems of ageing mums and dads – dementia, physical disabilities. I missed my dad but was grateful I’d been spared that torment.

Me aged three; Mum, Cambridge, 1975

Meanwhile my relationship with my mother was troubled and tumultuous – we’d been estranged for years after she became romantically involved with a man who treated me badly. But after my dad died, I felt a pressure to rebuild the mother-daughter relationship. I was acutely aware that she was the only family I had left.

By this time I had given up anthropology and was pursuing playwriting full-time. It made my mother very proud. The first time I had a play performed in the West End, in 2017, she dressed up, took me for afternoon tea beforehand then stuck her hand up during the post-show Q&A to ask the director, ‘Why are you not programming more plays from this incredibly talented young writer?’ I was mortified but also secretly pleased. I was happy that I’d made her proud of me. Little did I know that, within a couple of years, she too would be dead at 68 and I’d be alone in the world at the age of 37.

Mum and Dad in North Yorkshire, 1989

In May 2018, I was in Bristol attending a theatre conference. When the event ended I had a panic attack for no discernible reason and returned early to London. I wasn’t consciously thinking about my mum but worries about her – and her romantic relationship – were always in the background.

A few months earlier she’d told me that she’d phoned a domestic violence charity. They had put her in touch with a solicitor who specialised in such cases and was helping her to evict her boyfriend.

She told me that essentially they’d broken up, they slept in separate bedrooms and no longer had any real relationship; he was controlling and she was scared of him as well as what he might do if she told him to leave.

As a toddler, 1982

The morning after I got back from Bristol, I woke up to a voicemail from her number, but it was his voice on the recording telling me that she’d died. I got on a train to the hospital, where I viewed her body in the morgue, an incongruous apricot-frilled duvet cover hiding the black body bag underneath.

The coroner said the autopsy showed she’d died of a stroke, but when I spoke to her boyfriend the next day, he said the doctors had told him she’d be disabled if she lived, so had asked him to make a decision whether to resuscitate or not. He’d told them to ‘pull the plug’. Years later, one of the doctors who had treated her told me that was a lie.

Aged four, chasing ducks with Mum

To this day I don’t know what happened; only that my mother’s boyfriend returned to her house before her body was cold and tore the place apart looking for her will. When he found that she’d left everything to me, he squatted there for six months, padlocking the door as a final act of cruelty when he did a midnight flit to avoid being forcibly evicted.

If my father’s death had been tidy, my mother’s was as messy as her life. My beautiful, scatty, spiritual mum – who loved to sing as loud as possible and believed in feng shui and crystal healing – brought chaos with her as she lurched from drama to drama. And she left mayhem: not just her maisonette in Harrow, which was in ‘semi-hoarder’ condition, but legal and personal messes, too.

Aged 11, with my pet ‘Acorn Corny Rabbit’; a late-80s holiday in Israel

There was no space left for feelings. I closed my grief away but kept waking up crying. I used to get so angry when my friends complained about their parents’ minor flaws: at least you have parents, I would think. Be grateful and spend this precious time you have with them.

I felt guilty for not having done more to rescue my mother. After she died I found emails she’d sent to a friend, expressing a hope that I‘d turn up and whisk her away to a hotel. But I was also angry at her for not putting my needs first, for my having grown up a parentified child, forced to take on the role of a supportive adult. I needed to get over that anger before I could grieve.

With Mum in London, 1984

I was so traumatised and, perhaps overwhelmed by the enormity of my losses, afraid that my pain and bad fortune would be contagious, I closed myself off from old friends and others. The one thing that saved me was writing. In 2019, London’s Bush Theatre commissioned my play Unicorn, exploring my mother’s early life; I later wrote the award-winning interactive Batman, which invited the audience to participate in an onstage wake. Talking about grief, and writing about my mum, finally helped me to process all the emotions and feelings I’d been suppressing.

My theatre career took me all over the world, and I have used this as an opportunity to meet my mother’s unfulfilled desire to travel by scattering her ashes in nearly a dozen countries so far – including the Galapagos Islands in Ecuador, the Caribbean Sea off Mexico, the Seine in Paris, and of course the Thames in London.

In my favourite cardigan, 1987

She wasn’t the perfect mother, but she had some wonderful qualities. She never judged anyone and she had a profound love of animals, which I share. (I donated to Dogs Trust in her name.) I’ve always been very independent, and I live by myself, but loss made me realise how much I need people; that it’s OK to open up, accept love and care and ask for support. I’ve learnt how to use my writing to connect with others, to encourage communal grieving, and that brings me great joy.

My parents’ absence will always be a hole in my life, but their deaths have taught me that I am not alone.

With Dad in Eastbourne, mid-80s

Happy Death Club by Naomi Westerman is published by 404 Ink, £7.50. To order a copy for £6.75 until 18 August, go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937. Free UK delivery on orders over £25.