It’s been 35 years since the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum fell victim to the largest art theft in history.

In the early hours of March 18, 1990, two thieves disguised as police officers bluffed their way inside the Boston museum, tied up two guards, and made off with a dozen works estimated today to be worth more than $500 million.

Hundreds of suspects were eyed by investigators – from petty thieves to infamous mobsters – but no arrests have ever been made and the stolen art never recovered.

Among the first to fall under suspicion was Brian Michael McDevitt, a career conman who 10 years earlier in 1980 had attempted a near-identical caper at The Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, New York.

The Hyde’s executive director at the time, Frederick J. Fisher, told Daily Mail how McDevitt – masquerading as a member of the wealthy Vanderbilt family – hoodwinked him over several months while plotting to plunder the museum of more than 70 works.

Fisher believes McDevitt was the mastermind behind the Gardner heist and pointed to ‘glaring’ parallels between the unsolved robbery and McDevitt’s Hyde plot.

‘I’m absolutely convinced that he had something to do with that robbery,’ said Fisher.

‘The blueprints of the crimes are the same […] he was a con man extraordinaire.’

McDevitt’s ex-girlfriend Stéphanie Rabinowitz, agrees with Fisher.

She claims McDevitt confessed in 1992 to robbing the Gardner and asked her to give the FBI a false alibi.

‘He told me a man paid him $300,000 to rob the museum and he’d managed to do it,’ claimed Rabinowitz.

‘My gut instinct told me he was involved in this […] Why would somebody who is innocent make up all this crazy stuff and tell me the FBI is coming to see me?’

The Gardner Museum heist began at 1.20 am on March 18, 1990, when two crooks dressed as cops knocked on a side door and informed a security guard they’d received a report of a disturbance.

Against protocol, the guard, Rick Abath, led the two men inside.

The thieves approached the security desk and asked Abath to summon any other guards on duty to the lobby.

Randy Hestand joined Abath at the desk, and quickly the two guards were handcuffed, blindfolded with duct tape and dragged to the basement.

Motion sensors first detected the thieves entering the Dutch Room at 1.48 am.

They smashed an alarm system, ripped paintings from the wall and hacked the priceless pieces from their frames with blades.

The heist lasted 81 minutes and 13 pieces were stolen.

Two of Rembrandt’s renowned works were taken first: The Storm on the Sea of Galilee – his only seascape – and a Lady and Gentlemen in Black.

Two Rembrandt miniatures were also taken from the Dutch Room, along with Landscape With an Obelisk by Govaert Flinck, and The Concert by Johannes Vermeer.

The Concert is one of only 36 known works of Vermeer and is valued at $250 million. It remains the most expensive piece ever stolen.

Five works by the French impressionist Edgar Degas and Chez Tortoni by Edouard Manet were also snatched, along with a relatively valueless Chinese Gu.

The thieves were unable to remove all the screws from a case containing a Napoleonic flag and finally gave up, taking only the eagle ornament from the flagstaff.

Before leaving, the thieves broke into the security director’s office to steal the museum’s surveillance footage.

They exited the Gardner through the same door they entered at 2:45 am and fled the area in a hatchback.

Investigators have long been puzzled by why the crooks ignored valuable pieces and stole some worthless by comparison.

They didn’t even touch Titian’s The Rape of Europa, one of the most precious works in the U.S.

It led police to deduce the crooks were clueless amateurs rather than hired experts planning to steal specific pieces.

McDevitt quickly came into the crosshairs of investigators due to his foiled heist at The Hyde Collection.

The Hyde was modeled on the Gardner, and each museum contained works by Rembrandt, Vermeer, and other Old Masters and French Impressionists

Fisher became the executive director of The Hyde Collection in 1978 and first met McDevitt in the fall of 1980.

McDevitt introduced himself to Fisher under the alias Paul Sterling Vanderbilt, claiming to be an heir to the Vanderbilt fortune and a freelance writer for influential magazines and newspapers.

Unbeknown to Fisher, McDevitt had recently stolen $100,000 from the lockbox of a Boston attorney and was using the funds to finance his plan to rob the Hyde.

‘He was the talk of the town,’ Fisher remembered of McDevitt, who was 20 years old at the time.

‘He was driving a Bentley. He was dressed very well, spoke very well, and told me he wanted to get to know us because he thought he might be able to do something for the museum.’

McDevitt asked Fisher if he could rent a room next to the museum and join The Hyde’s board as a trustee.

He also said he was writing an article about art theft and began inquiring about the museum’s security features.

He went so far as to go into the city’s planning building and ask to see blueprints of The Hyde.

The planning office refused and alerted Fisher, who contacted the police.

‘He kept doing more things in the local community that told me something about him wasn’t right – that he was up to something,’ said Fisher

‘McDevitt stuck out like a sore thumb.’

Still, McDevitt persisted in attempting to ingratiate himself with Fisher.

A week before Thanksgiving, he showed up at the museum bearing gifts: three IBM Selectric typewriters that the museum had been in desperate need of.

Fisher would later discover McDevitt had rented them from an electronics store in New York.

He confronted McDevitt, who acted outraged at the accusation and told Fisher he’d planned to donate $30,000 to The Hyde.

McDevitt’s true intentions would be revealed in a matter of weeks.

Three days before Christmas, McDevitt with the help of Michael B. Morey – a local man he’d blackmailed into assisting him – set a plan into motion to ransack the museum.

The pair contacted FedEx and asked for a truck to be sent to a garage in South Glens Falls to retrieve a package.

When the driver arrived, she was forced back into the truck at gunpoint, handcuffed, blindfolded and muzzled with tape, and incapacitated with an ether-soaked rag.

The two men disguised themselves as FedEx workers and planned to empty the museum by cutting pieces out of their frames with razor blades.

However, one thing McDevitt failed to account for in his months of planning was holiday rush-hour traffic.

They arrived at the museum minutes after it closed and were forced to abandon their plan.

The FedEx worker they’d subdued called police and later identified both men as the culprits, who pled guilty.

McDevitt was convicted of unlawful imprisonment and attempted grand larceny. He served several months of a two-year sentence in the Saratoga County Jail.

Years later, when Fisher learned of the details of the heist at the Gardner, he immediately thought of McDevitt, noting a series of stark similarities between each crime.

The Gardner robbers disguised themselves as cops, whereas McDevitt and Morey posed as FedEx workers; handcuffs and tape were used to shackle, blindfold, and gag hostages in each crime; gloves and blades were chosen to cut the art out of its frame; and both sets of thieves appeared to have detailed knowledge about the layout of each museum.

Further, Fisher highlighted that in both cases the crooks were sympathetic to their hostages, with the Gardner thieves making sure Hestand and Abath were fine before they left, and the female FedEx worker being repeatedly assured by McDevitt that she wouldn’t be harmed.

Fisher believes McDevitt’s fingerprints are all over the Gardner heist, and he was either one of the two crooks or possibly helped orchestrate the caper.

At least one of the Gardner robbers was also described as speaking with a Boston accent, as did McDevitt.

McDevitt was living in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood when the Gardner Museum was robbed in 1990.

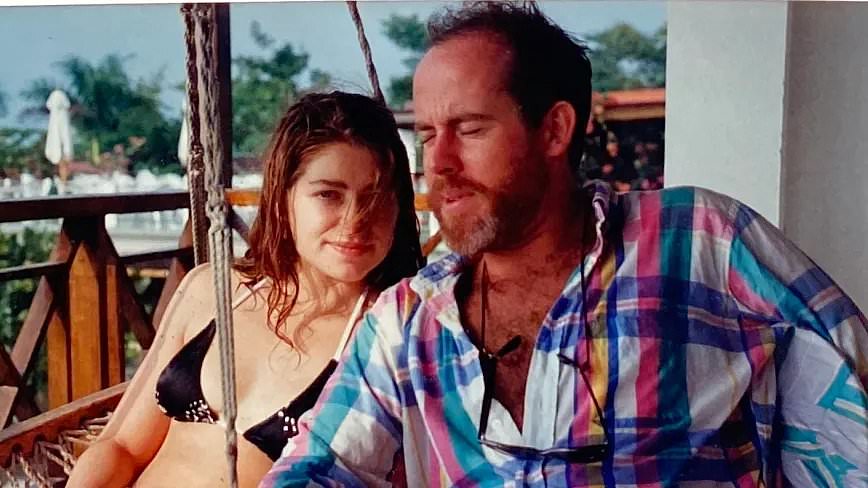

He began dating Stéphanie Rabinowitz a few months prior, who was then in her mid-20s.

The pair met in July 1989 at a comedy club, with McDevitt claiming to be a hotshot Hollywood writer for Paramount and Columbia Pictures.

Rabinowitz kept a detailed diary. In excerpts in the days leading up to the Gardner heist, she wrote that she and McDevitt were having relationship issues, and described him as hostile and aggressive.

Then on March 15, Rabinowitz said McDevitt told her he was leaving for a few days to attend the Writers Guild of America Awards in New York.

She didn’t hear from him again until late on March 18 – hours after the Gardner was pillaged – and by then described him as seeming calmer and more like his usual charming self again.

Soon after, McDevitt told Rabinowitz he needed to move to LA and asked her to come with him.

Rabinowitz refused but they kept in touch.

McDevitt, meanwhile, packed up his belongings and drove himself from Boston to LA in a U-Haul, setting off in the middle of the night without notifying his neighbors.

After arriving on the West Coast, McDevitt continued to tout himself as a hotshot writer and soon struck up a friendship with a screenwriter named Ben Pollack.

Pollack shared that he was shocked at the lack of quality in McDevitt’s writing, particularly for someone who claimed to have experienced so much success.

Then, one day, McDevitt pitched him a script idea about two bumbling thieves who successfully rob an art museum.

In McDevitt’s plot – which closely mirrored the Gardner caper – the thieves stole several priceless paintings and two metal statues. They planned to sell the stolen art to a foreign buyer and hid their loot in a cave until a deal was made.

But when the deal fell through, the thieves realized they had nobody to sell the art to and were forced to destroy it.

Both Pollack and Rabinowitz believe McDevitt’s script idea was a thinly veiled confession and may hold clues as to the fate of the Gardner loot.

‘There’s no doubt in my mind he did this,’ said Pollack in 2024 of McDevitt and the Gardner heist.

‘He was the smartest idiot I’ve ever encountered […] That script idea told us exactly what happened: he pulled off the heist, somehow, and destroyed and buried the art when he couldn’t sell it.’

Within months of meeting McDevitt, Pollack sensed something off about him and hired a private detective to dig into his past.

He soon learned that nothing McDevitt had told him was true and confronted McDevitt about his lies.

McDevitt responded by threatening and harassing Pollack for months, and by the summer of 1992 McDevitt was facing criminal charges for harassment.

That same summer, he was named as one of the prime suspects in the Gardner case in a New York Times report.

In the article, McDevitt denied any involvement and revealed he’d been questioned and fingerprinted by investigators. He was also asked to take a polygraph test but refused.

McDevitt also told The Times he had an alibi for the night of the crime: he was with a woman he was dating, who would attest to his innocence.

When the article was published, Rabinowitz claims McDevitt contacted her to warn ‘there’s a good chance to FBI’ was coming to speak with her and asked her to provide a false alibi on his behalf to investigators.

‘He asked me twice to be his alibi and he got really mad when I said I wouldn’t do it,’ recounted Rabinowitz.

‘You could tell he was fuming […] But I wasn’t going to lie to the FBI.’

The last time Rabinowitz ever saw McDevitt was at a wrap party for a show she was working on in LA, in July 1992.

During a brief catch-up, Rabinowitz claims McDevitt made a startling confession: he had been paid $300,000 to rob the Gardner and needed to leave the country immediately because federal investigators were closing in.

McDevitt said he was fleeing to South America and wanted Rabinowitz to move with him, promising he had enough money to live out the rest of their days in comfort.

Stephanie declined McDevitt’s gesture.

She has been interviewed twice by the FBI, once in 1992 and again in 2004, when she shared her diary entries with investigators for the first time.

McDevitt was also questioned twice and, in August 1993, testified before a grand jury.

He high-tailed out of the U.S. to South America shortly after and died in Bogota, Colombia, in 2004 from apparent kidney failure.

Rabinowitz said she isn’t convinced McDevitt is really dead.

Fisher shares Rabinowitz’s suspicions.

Thirty-five years on, a $10 million reward posted by the Gardner Museum for the missing art’s safe return remains unclaimed.

Empty frames solemnly hang in the place where the works once were.

Gardner Security Director Anthony Amore, who for years worked in close association with the lead FBI investigator Geoff Kelly, said he doesn’t believe McDevitt was involved in the infamous heist, citing privileged information shared by the FBI.

Amore believes he and Kelly know who perpetrated the crime: two petty thieves with connections to Mafiosos in Connecticut and Philadelphia.

He declined to name the individuals but said both are dead.

What he and Kelly don’t know is where the artwork is.

‘Every day we work on this we’re getting closer to solving it,’ an optimistic Amore told Daily Mail.

‘It’s sort of like we have 13 needles in a haystack, and every time we follow a lead, we’re able to make that haystack smaller.’

Something that has divided investigators over the years is whether or not the stolen Gardner art is still intact.

Amore believes it is. He pointed to the more than 1500 heists he’s studied, adding: ‘You’d be hard-pressed to find one where the paintings – especially masterpieces – were truly destroyed.’

‘I’ve spoken to countless people in the criminal underworld and policing, and none of the people who would’ve been informants has ever told us they heard the paintings were destroyed […] so I’m hopeful they’re out there and we will get them back.’

The lack of credible sightings over the years leads Amore to believe the 13 missing pieces haven’t strayed too far from the Northeast.

He urged the public to study pictures of the missing works, believing a tip from an everyday citizen is a viable way of solving the case once and for all.

Asked whether he ever allows himself to envision the moment the Gardner collection is restored to its former glory, Amore said he tries to not let his imagination get the best of him.

‘It does enter my mind but I try not to focus on it,’ he said.

‘I have other things to worry about at the moment – and that’s finding this art.’